Calculated Need: Algorithms and the Fight for Medicaid Home Care (Fact Sheet)

Miriam Osman, Emily Paul, Emma Weil

Fact SheetUpturn’s new report, available at upturn.org/work/calculated-need, is a deep dive into the algorithms that states use to determine eligibility for Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS). Our report includes an in-depth analysis of eligibility algorithms in five states (Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Jersey, and Washington, DC); case studies on how three of these states’ Medicaid agencies worked with vendors to develop their algorithms; and historical research on the emergence of the institutional level of care as the federally mandated eligibility standard.

What is a LOC algorithm?

To be eligible for HCBS, federal guidelines state that individuals must be determined to require a level of care, or LOC, that would otherwise only be met in an institutional setting. Yet there is no standard definition for this institutional level of care. Rather, it is left up to each state to define through rulemaking and work with private vendors.

LOC algorithms implement each state’s regulatory definition of the level of care. A LOC algorithm takes an individual’s ratings on a standardized face-to-face assessment and uses logic to produce an eligibility determination. When designing their LOC algorithms, state agencies and vendors may choose different subsets of assessment questions to include and may assign different weights or scores to those questions and responses. A state may include only Activities of Daily Living (e.g., eating, bathing, and toileting), for example, or it may add other factors such as cognition or balance issues. It then uses points or profiles to determine if someone meets the eligibility standard. States’ design choices can create meaningful differences between a state’s regulatory language and how people are actually determined eligible for HCBS. Further, these choices vary significantly across states, so every state’s LOC algorithm looks different.

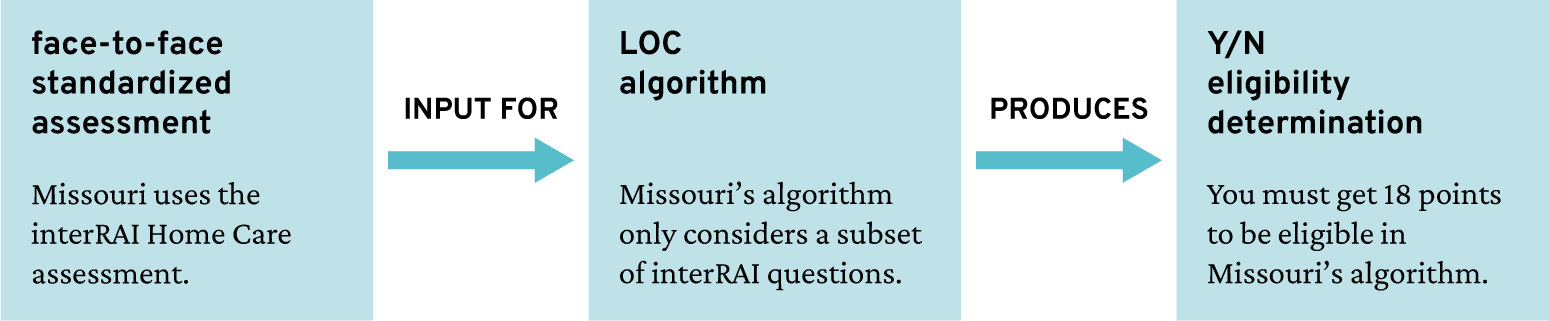

The HCBS eligibility determination process, using Missouri as an example

This graphic illustrates the HCBS eligibility determination process, using Missouri as an example. The graphic shows face-to-face standardized assessment as an input for the LOC algorithm produces Yes/No eligibility determination. In this example, Missouri uses the interRAI Home Care assessment while Missouri’s algorithm only considers a subset of interRAI questions, which in turn requires 18 points in order to be eligible.

Why does the level of care look so different across states?

LOC algorithms look so different across states because they are not actually designed to meet people’s needs. Rather, they serve the policy and budget goals of each state’s HCBS program. These goals are tied to the original purpose of the program, which was to reduce government spending on long-term care by creating a subjective and arbitrary definition of who “deserves” it. States make different choices to control the composition and overall size of the eligibility group. This means that someone who is considered eligible for HCBS in one state may not be eligible in many other states. In our report, we conducted an analysis comparing eligibility across five states, using assessment data from a real person who lost eligibility in Missouri. Because of the variety of LOC definitions and algorithm design choices, we found that the same person, with the same needs, was eligible in Nebraska and Mississippi, but not New Jersey, Missouri, or Washington, DC.

How does the use of automation undermine access to care?

Not only can LOC algorithms deny care to people who should be eligible under their state’s regulations, but states’ reliance on automated tools also can undermine the fight for access to home care. States’ use of automated tools and reliance on private vendors obscures the political question of the right to care as a technocratic question of how to measure eligibility. States do this by:

Focusing on accuracy: State agencies claim that their automated determinations can identify the “right people.” In reality, the level of care is used like a dial to control eligibility rates.

Deferring to vendor expertise: Vendors’ standardized assessments and recommendations heavily influence state rulemaking and algorithm design.

De-emphasizing the role of the algorithm: In public materials, state agencies rarely discuss the extensive and subjective process of developing the algorithm.

Concealing assessments and algorithms from the public: Vendors’ proprietary interests shield algorithms from scrutiny, even in the face of due process claims.

The idea of LOC … being clear-cut is a myth.

Meeting minutes between vendors and Nebraska state employees

How should advocates approach this problem?

Through our research and technical assistance to legal services organizations, we have concluded that there are no “good” Medicaid HCBS eligibility algorithms—just those that are more or less harmful. While tweaking an algorithm to expand eligibility is a critical way to reduce harm, it will, by definition, never resolve the political problem at the heart of HCBS, which is that access to these services is not yet a right. As such, advocates should approach algorithms as political tools, so that efforts to address algorithmic harms are connected to broader fights for universal care—which we believe is the only system capable of meeting people’s needs.

In this report, we provide practical recommendations for advocates in challenging eligibility determinations. Our report recommends ways to learn more about each state’s LOC algorithm, understand its impact, and mount collective challenges against it. We also include a list of questions to ask that can help advocates analyze these algorithms and the ways they are being used in each state. Finally, we encourage advocates to reach out to the Benefits Tech Advocacy Hub when seeking free technical assistance. We believe relationship and coalition building is a critical component of growing collective power. Fill out our intake form to get started: bit.ly/benefits-ta

This work would not have been possible without our Benefits Tech Advocacy Hub partners, TechTonic Justice and the National Health Law Program, and the legal services organizations that introduced us to this topic and generously shared their expertise with us.

Related Work

Our report on eligibility algorithms for Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services found that automated eligibility determinations are not designed to meet people’s needs. Rather, they are political and budgetary tools designed to control access to state-provided home care benefits.

Public BenefitsWe’re partnering with Legal Aid of Arkansas and the National Health Law Program to provide tools for advocates to fight harmful benefits technology and to build a community of advocates and technologists working to challenge tech that keeps people from accessing benefits.

Public BenefitsA follow up on the July 13, 2021 letter sent to Assistant Attorney General Kristen Clarke, then-Secretary of Labor Martin Walsh, and then-OFCCP Director Jenny Yang titled Addressing Technology’s Role in Hiring Discrimination (the “2021 letter”) and the “Automated systems, including artificial intelligence (AI)” section of the October 26, 2023 letter sent to the EEOC.

Labor and Employment Jobs and HiringOur paper on how entities that use algorithmic systems in traditional civil rights domains like housing, employment, and credit should have a duty to search for and implement less discriminatory algorithms (LDAs).

Across the Field