According to the Washington Post, police officers shot and killed 987 people in the U.S. in 2017.

The Post has tracked fatal police shootings since 2015, collecting more than a dozen details about each incident including the victim’s race, age, gender, whether the victim was armed, and whether the victim was fleeing from officers. The Post also tracks whether or not “[n]ews reports have indicated an officer was wearing a body camera and it may have recorded some portion of the incident.”

The Post found that only about a tenth (100 of 987) of last year’s fatal police shootings were likely recorded by at least one body-worn camera. (We came across a few more cases, which are reflected in the numbers referenced in this article.)*

Law enforcement and the public have widely praised body-worn cameras as transparency tools. Concern about these fatal encounters, and about officers’ excessive use of force, is a key driver of camera adoption. Upturn has long tracked policies and practices around body-worn cameras, but so far, we’ve seen little indication that these tools truly increase transparency of police conduct. The Post’s data gives us an opportunity to test this supposition.

If body-worn cameras are indeed meaningful transparency tools, we would expect to see the videos of police shootings — the most serious interactions between law enforcement and civilians — consistently shared with the public, within a reasonable time after the incident.

We reviewed various local and national media reports following each of the fatal police shootings from 2017 that the Post marked as likely recorded by a body-worn camera. We gathered data about whether footage from each incident was released to the public, after how long, and under what circumstances.

As we analyzed the results, we focused on four questions:

Is footage publicly released? Do police departments actually share video from fatal shootings with the public?

Is footage release timely? Is video released as soon as possible, or is it withheld for an extended period?

Is footage release consistent? Is video from a jurisdiction always treated the same way, or does it vary by incident?

Is footage release mandatory? Does a binding policy or law compel footage release under a clear set of written guidelines?

Is body-worn footage of fatal police shootings released?

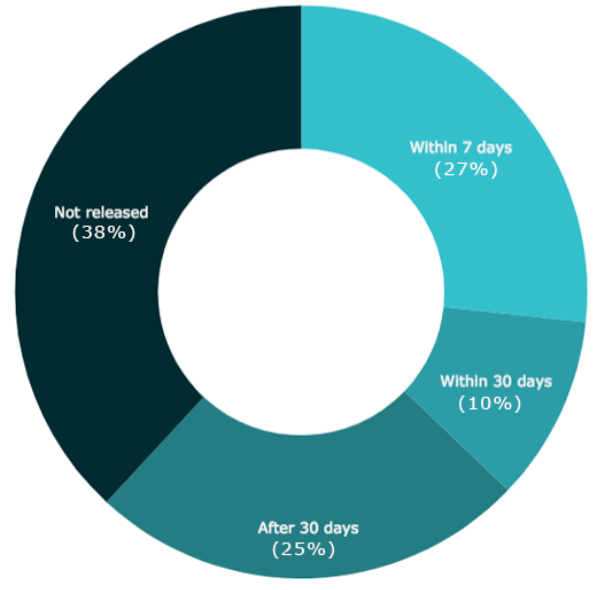

We found that, of the 105 police killings captured by body-worn cameras last year, footage was not made public in 40 of these cases.

Figure 1.

Days until release of available body-worn camera footage, for all fatal police shootings in 2017.

While a slight majority of footage was released eventually, claims of transparency seem fundamentally unfulfilled, given that departments fail to make footage public in such a large portion of police shootings.

Is body-worn camera footage release timely?

Among the 65 cases where footage was made public, the median time to release was nine days after the incident. In three cases, including the fatal shooting of Eric Garrison in Baltimore, departments released footage on the same day as the incident.

In 26 cases, though, videos were not released until month afterward or later. Footage from Andrew Byrd’s fatal shooting in Pueblo (CO) wasn’t released for 276 days, the longest time span we observed.

Police chiefs and district attorneys frequently postpone release, claiming that making video public would undermine the integrity of an investigation or taint a jury pool. But the relatively short median footage release time suggests plenty of departments are able to share footage well before full investigations are complete. Our data indicates that a substantial number of jurisdictions have concluded they can protect investigations without withholding footage until the very end. The New Jersey Supreme Court concurred with this assessment in 2017 (in the closely related context of dashboard camera footage), finding that “[u]nder the common law, the public’s powerful interest in disclosure of that information, in the case of a police shooting, eclipses the need for confidentiality once the available, principal witnesses to the shooting have been interviewed,” and noting that “[i]n an ordinary case, investigators take statements from those witnesses soon after an incident, while the events are fresh in mind.”

Nevertheless, in many cases we reviewed, footage was only released after investigations were adjudicated — in most cases, along with an announcement that the officer under investigation had been cleared of all wrongdoing.

Is body-worn camera footage of police shootings consistently released?

We were encouraged to see some departments regularly sharing video from all recorded incidents, often within a defined timeframe.

After all five of the fatal police shootings in Las Vegas that were recorded by body-worn cameras, the department consistently shared the relevant footage within three days. For each incident, the department held a press briefing to screen the body-worn camera footage, and later posted the video of the briefing to the department’s YouTube channel.

The San Francisco Police Department likewise released videos from both of its recorded fatal police shootings in 2017, showing the video at town hall meetings and posting it online. While SFPD’s policy doesn’t mandate a specific release timeline, it does stipulate that the “goal is to release BWC recordings to the greatest extent possible unless disclosure would: a. endanger the safety of a witness or another person involved in the investigation, b. jeopardize the successful completion of an investigation, or c. violate local, state and/or federal laws, including but not limited to, the right of privacy.”

Baltimore and Louisville police too shared shooting footage within days; Oklahoma City’s video releases all fell within a month of the original incidents.

Other departments appeared to be more irregular in their practice, releasing video from some incidents quickly and others more slowly — if ever. Las Cruces shared footage from one shooting after 29 days, but for another, waited 72 days. Fresno shared footage from one incident but withheld entirely it in another. (Many departments had only one fatal shooting in 2017, so consistency of practice could not always be determined.)

Is footage release mandated by policy or law?

Some police departments are compelled to release footage by state or local laws or policies. The strongest such policies mandate the release of critical footage within a certain number of days.

As far as we know, among major cities, only Chicago currently has such a written policy, adopted following the highly publicized shooting of Laquan McDonald in 2014. Chicago’s policy requires footage from officer-involved shootings to be released within 60 days of the incident, with the possibility for a 30-day extension in limited circumstances. The city posts these videos online on Chicago’s civilian police oversight website.

Even with this policy in place, Chicago already defied its own rule last year, when it withheld footage from the nonfatal shooting of Dwane Rowlett beyond the 90-day limit. In a more recent case, though, the city released footage of Aquoness Cathery’s fatal shooting after exactly 60 days, in accordance with the policy.

The Los Angeles Police Commission, which governs the second largest police department in the country, is currently weighing a proposed policy that mandates critical footage release within 45 days. The new policy would reverse the department’s longstanding practice of withholding all footage unless there is a court order. The Commission’s proposal builds on the positive elements of Chicago’s policy, and is the strongest example of a mandatory release policy we’ve seen so far.

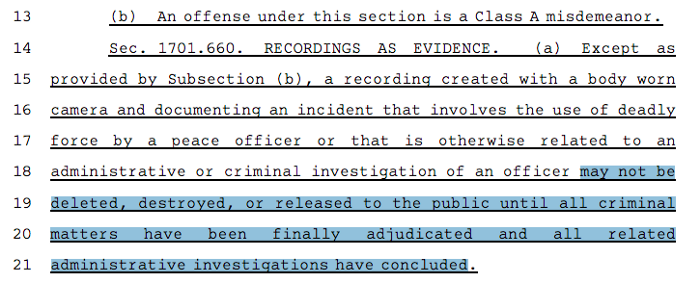

In contrast, a few states like Texas prohibit video release until all criminal and administrative investigations have been completed.

Texas S.B. 158

Texas S.B. 158 (emphasis added)

Equally troubling, North Carolina requires a court order to release footage — even in cases where police agencies want to make the footage public. While laws like these may allow release of body-worn camera footage in certain narrow circumstances, they force a wholesale, statewide shift away from policies that facilitate more transparency.

Public pressure can overcome mandatory constraints in some cases, forcing departments to go public with footage when they might have opted to withhold it. When 38-year-old Alva Braziel was shot and killed by Houston Police Department officers on July 9, 2017, Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner chose to release video of the incident “because of the exigent circumstances that we find ourselves in.”

Both Mayor Turner and Acting Houston Police Chief Martha Montalvo were very careful to point out that they were not required to release the footage, and that they were exercising their discretion only because of exigent circumstances and a concern for public safety.

In many states, public records laws nominally provided access to body-worn camera footage. Some of the video releases we observed happened through such channels, but these laws have been largely ineffective drivers of transparency after critical cases like police shootings. Where body-worn camera footage is classified as a public record, members of the public or journalists still need to request footage from departments, which they can subsequently publish. Because such disclosures are contingent on external requests, actual release practices under public record regimes can be inconsistent — especially where departments lack a separate policy to proactively share footage from use-of-force incidents. Worse, many police departments have routinely and categorically claimed available exemptions in public records laws to deny external requests for what they consider investigative records or violations of personal privacy, or charge demand exorbitant fees to fulfill records requests. Groups like the NYPD’s largest police union have tried to systematically undermine public records laws, claiming that body-worn camera footage is a police personnel record and thus never appropriate for public disclosure.

While public records laws may require disclosure in theory, these carve-outs weaken the power of public records laws to ensure transparency of body-worn camera footage, especially after police shootings. Such laws should not be mistaken for true mandatory release instruments, under which body-worn camera video is presumptively shared with the public on a defined timeline.

. . .

A 2017 survey found that 88 percent of Los Angeles residents believed that video should “definitely” or “probably” be shared with the public. Another survey found that a majority of New Yorkers believe the NYPD should release footage of high profile incidents “as soon as possible.”

Yet our findings show that we cannot assume police departments will make body-worn camera footage publicly available, even after the most serious cases like fatal police shootings. Body-worn cameras cannot be meaningful transparency tools without mandatory, consistent, and timely disclosure of footage from these events.

This analysis is just a starting point. We focused here only on the narrow but important scope of fatal police shootings. But body-worn cameras capture many more incidents that have a dramatic effect on people’s lives, including thousands of nonfatal police shootings and other uses of extreme force each year. Such incidents are not uniformly tracked around the country, making it difficult to measure the extent to which footage is made public after those incidents. Nevertheless, given that body-worn camera footage is far from universally released even in the most serious cases, we believe that the state of transparency is far worse for nonfatal uses of force.

At the very least, local governments and departments need to consider, enact, and enforce mandatory release policies for police shootings, where transparency is paramount. While some police departments are on the right track, in far too many cases footage is still withheld from the public outright, or withheld for much longer than is reasonably necessary. If we believe that body-worn cameras should shine a light on the most critical cases — regardless of whether or not the police officers’ behavior was legal and justified — mandatory footage release policies should be considered a prerequisite for every department with a camera program.

*Our numbers slightly differ from the Post’s; during the course of our research, we identified several additional shootings that media sources reported as having been recorded by at least one body camera, as well as a few where video flagged in the Post’s data was fixed surveillance footage rather than BWC footage. Other shootings in 2017 may have been captured on body-worn cameras but were not correctly marked in the Post’s data. Because we conducted our research in early 2018 (the data is current as of February 22), it is possible that figures could continue to change as more footage from last year is released.

Harlan Yu contributed research to this article.

Related Work

We wrote a letter to Axon’s AI Ethics Board to express serious concerns about the direction of Axon’s product development, including the possible integration of real-time face recognition with body-worn camera systems.

PolicingToday, most major police departments that use body-worn cameras allow officers unrestricted footage review. This report explains why police departments must carefully limit officers’ review of body-worn camera footage, and calls for “clean reporting” to be adopted by all police departments.

PolicingUpturn files an objection to the NYPD’s proposed body-worn camera policy, together with the Leadership Conference, the Center for Media Justice, Color Of Change, and other groups.

PolicingTogether with the Leadership Conference, Upturn releases the latest version of our scorecard that evaluates the police body-worn camera policies in 75 major U.S. cities. It continues to show a nationwide failure to protect the civil rights and privacy of surveilled communities.

Policing