We responded to the Federal Trade Commission's request (FTC-2023-0024) for information on tenant screening technologies, demonstrating how they drive housing insecurity and discrimination. We submitted the following statement via regulations.gov on May 30, 2023.

Executive Summary

Tenant screening reports drive housing insecurity and discrimination by entrenching criminal, credit, and eviction histories as universal barriers to housing. Tenant screening companies’ core function is to repackage credit, criminal, and eviction histories. Their business model and rhetoric perpetuate the narrative that people with certain backgrounds don’t deserve dignified housing. These practices drive racial and other forms of housing discrimination.

Tenant screening companies make housing decisions, automate rejections, and encourage landlords to rely on them. Tenant screening companies automate housing discrimination by using eviction, credit, and criminal histories as a basis for making eligibility determinations — such as scores, predictions, and recommendations. They intentionally design their reports, services, and marketing to encourage landlords to rely on their interpretations and conclusions.

Tenant screening reports undermine policies and funding aimed at improving access to housing. Federal, state, and local governments — as well as community organizations, tenant organizers, and direct service providers — spend significant money and resources to improve equitable access to housing, make housing more affordable, and enforce fair housing laws. But the efficacy of these efforts hinges on people actually being able to get housing. Screening out tenants based on background checks undermines efforts to improve access to fair and affordable housing.

“Objectivity” and standardization in tenant screening do not protect against discrimination. Tenant screening is based on fundamentally discriminatory information and on racist, anti-poor, anti-renter political decisions about who deserves to choose where they live. Federal agencies should limit the information that can be used to screen tenants, but the government should avoid establishing a set of criteria that it deems “fair” or “objective” for screening out renters. The burden should always be on housing providers and screeners to rigorously justify any criteria or information they use to deny someone housing.

Existing remedies leave large gaps in renter protections and enforcement. Existing protections are too limited in scope and enforcement. Enforcing tenant screening protections often requires information, time, and resources that renters — and often legal service providers — don’t have access to. The whole federal government must work to fill these gaps, but the FTC is particularly well positioned to enforce against tenant screening companies’ unfair and deceptive practices and to ensure that renters are preemptively protected from discriminatory tenant screening reports.

Summary of recommendations

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) should use its authority under Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act (“FTC Act”) to enforce against unfair and deceptive tenant screening practices. The FTC should prioritize enforcing against tenant screening practices that are likely to have discriminatory impacts. The FTC should also consider issuing guidance clarifying what constitutes an unfair or deceptive tenant screening practice.

The FTC should enforce against unfair tenant screening practices including:

Screening out tenants based on criminal, eviction, and credit histories. These practices reproduce housing discrimination and unjustifiably limit access to housing. The FTC should enforce against tenant screening companies’ and landlords’ reliance on these records as screening criteria, including their dissemination in tenant screening reports and incorporation into scores and recommendations.

Making and disseminating tenant screening reports, scores, and other eligibility determinations that encourage landlords to reject housing applicants without an individualized assessment. Tenant screening companies use algorithms to produce scores, risk predictions, and recommendations about tenants’ “eligibility” that collapse any context or nuance in tenants’ backgrounds. These features encourage landlords to apply rigid rules that deny tenants an individualized assessment and an opportunity to provide mitigating information. As FTC Commissioners have recognized, the FTC is well positioned to address the unfair design and use of algorithms and “predictive” technologies in tenant screening.

The FTC should also enforce against deceptive tenant screening practices, including the misrepresentation of information within tenant screening reports, and misleading representations about their ability to predict tenant outcomes and behavior.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) should clarify that tenant screening companies’ record matching practices don’t meet reasonable accuracy standards under the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA). Two practices in particular raise substantial accuracy concerns:

Matching and reporting court records. Matching and reporting on civil and criminal court records is unavoidably inaccurate and must end.

Relying on automated processes to match and include records on tenant screening reports. The CFPB has observed that most tenant screening companies appear to rely on fully automated matching and don’t regularly conduct manual checks to ensure the accuracy of the records they report. The CFPB should clarify that these practices violate consumer reporting agencies’ (CRAs’) accuracy obligations.

The CFPB should consider whether tenant screening companies’ reports and eligibility determinations represent abusive practices under the Dodd-Frank Act. Eligibility determinations can “overshadow” underlying data, which can materially interfere with a landlord’s understanding of the product.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) should provide guidance and enforcement against discriminatory tenant screening practices under the Fair Housing Act.

HUD’s guidance on criminal record screening has raised landlords’ and tenant screeners’ awareness that their use of criminal records can be discriminatory and unrelated to tenancy outcomes. HUD should extend the reasoning in its criminal records guidance to address screening based on eviction and credit histories.

HUD should also clarify, through guidance and enforcement, that providing eligibility determinations in tenant screening reports violates the Fair Housing Act. Eligibility determinations, such as scores and predictions, are susceptible to disparate impacts, and they make it impossible to conduct the kind of individualized, fact-based assessment required to determine whether they are necessary to achieve a substantial, legitimate, nondiscriminatory interest.

Introduction

Housing is an essential survival need, but to access rental housing, almost every renter must undergo and pay for an application and background check (usually several). At the end of this process — often after paying hundreds of dollars in fees and searching for months — many people are still left without homes, even if they can afford rent. Landlords, usually relying on tenant screening reports, systematically screen out applicants based on information like criminal, eviction, and credit histories, all of which are artifacts of structural discrimination and should not be used to deprive people of housing. The majority of tenants who are locked out by background checks have little effective recourse for these harms — existing laws leave large gaps in renter protections and enforcement.

Tenant screening technologies exacerbate these harms by further entrenching discriminatory information into the tenant screening process, automating discrimination by making eligibility determinations for landlords, and obscuring the nature and flaws of underlying records.

Barriers to housing are only intensifying as housing costs rise well beyond wages, governments cut pandemic-era funding for programs like rental assistance and eviction defense, evictions continue apace, and landlords ratchet up their eligibility standards. Tenant screening also deadens the impact of federal, state, and local funding (such as vouchers) aimed at increasing access to fair and “affordable” housing.

Tenant screening gives landlords and consumer reporting agencies (CRAs) the power to decide who is worthy of a home, leaves people homeless, and causes housing subsidies to go unused. Our systems for distributing housing must be transformed, but in the meantime, the Biden-Harris administration must acknowledge that today’s tenant screening practices are inconsistent with its stated goals of increasing fair and affordable housing. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) must use the full extent of their authority to protect people from the harms of tenant screening, especially its discriminatory impacts.

This comment describes the role of tenant screening reports, records, and eligibility determinations in the tenant screening process, and their impacts on individual renters and on access to housing more broadly. It recommends actions for the FTC and CFPB to take under their respective authorities, as well as actions for the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to take under the Fair Housing Act.

I. The tenant screening process

Tenant screening is any process by which a landlord evaluates and decides whether to accept or reject potential renters, or to accept them with conditions (such as a higher security deposit). Usually, landlords use information provided by the applicant, such as their income, as well as public and proprietary records from third-party sources. Renters are often screened based on income (often rent-to-income ratio), criminal history, credit history, and rental (or eviction) history. Many landlords use tenant screening services, which use automated processes to conduct background checks and create tenant screening reports. Tenant screening can be broken down into a few steps, which we summarize below.

A. Criteria selection

Tenant screening companies either fully determine the criteria used to screen applicants, or co-create the criteria with their landlord clients. They usually design and sell tenant screening reports that include some credit history, rental history (including evictions), and criminal history. Reports might also include other elements like income verification, rent-to-income ratio, and employment history. A few services advertise less common features, such as predictions about specific tenancy outcomes, like lease terms or pet liability.

Many tenant screening companies assign scores or other eligibility determinations to tenants. There is little public information about how tenant screening companies generate these recommendations. In some cases, it appears that a single factor, such as an arrest record or eviction filing, can trigger a conclusion that a tenant is unqualified. Often, tenant screening companies use a proprietary formula, based on multiple screening criteria, to calculate a three-digit score and provide a high-medium-low score range to convey the applicant’s eligibility or relative risk.

Some tenant screening services offer customization options for their landlord clients. For example, CoreLogic provided a list of categories of criminal records and allowed landlords to choose which ones would be used as screening or disqualifying criteria. RentPrep provides a sample tenant screening criteria form that includes a suggested minimum credit score (620) and rent-to-income ratio (three times the monthly rent), and lists items that “can be considered a deniable factor.”

B. Application and fees

Landlords initiate tenant screening by requiring potential renters to submit an application and pay an application fee. Some landlords accept applications (and fees) from multiple renters and choose among them, while others may only accept one application at a time and/or rent to the first qualified applicant. Applicants are asked to provide personal information — such as their names, date of birth, previous addresses, and their Social Security number — that can be used to run a background check. Some landlords create their own application forms, but often they use a tenant screening service’s application portal and forms.

Landlords usually charge applicants a non-refundable fee, and renters often pay multiple non-refundable application fees before finding a home. A study by Zillow found that Black, Latine, and Asian American and Pacific Islander renters pay an average of $50 per application fee compared to $35 for white renters, and that renters of color are almost twice as likely to submit more than five applications before finding a place to live.

Tenant screening companies encourage landlords to pass on the cost of the tenant screening service to rental applicants; however, landlords often do not disclose or itemize how they use the fees they charge, or how the amount of the application fee relates to the landlord’s actual tenant screening costs. While the cost of tenant screening services can vary widely, some landlords — especially larger ones with tenant screening subscriptions — may only pay a few dollars for each report, and there is evidence that some landlords use application fees as a source of profit.

C. Matching

Fundamentally, all tenant screening companies create their reports by attempting to match the rental applicant’s personal information with records in various public and private databases. The sources of these records include public court websites, credit files from nationwide consumer reporting agencies (NCRAs), and data that tenant screening companies purchase from other data brokers, which may be held and maintained by the tenant screening company itself or by a third party.

Tenant screening companies use algorithms, sometimes referred to as “matching logic,” to search databases and retrieve records that have information that matches (or partially matches) one or more pieces of personal information provided by the rental applicant. For example, “name-only matching” refers to the process of searching for, and then including in a tenant screening report, records that match the name of the rental applicant, regardless of whether any other information in the record (such as address, Social Security number, or the date the record was created) can be verified as matching the rental applicant’s profile. TransUnion SmartMove’s marketing language suggests that it uses tenants’ names and addresses to match them with records.

At least some tenant screening companies may be relying on fully automated processes to match rental applicants to records and include those records on tenant screening reports, without manually checking for even the most obvious accuracy problems, like mismatched personal information or missing case dispositions. In its Tenant Background Checks Market Report, the CFPB observed that “most tenant screeners[] . . . appear to rely on the low-cost automated retrieval of court records for criminal and eviction records, without the more costly manual verification needed to ensure accuracy.”

D. Categorizing, labeling, and interpreting information in a report

Tenant screening companies modify, interpret, and assign priority or value to the information they surface from records and include in tenant screening reports. For example, the information and offense types listed in criminal records vary widely by jurisdiction, so background check companies usually sort them into a smaller number of uniform categories and attach labels to them, like “traffic” or “felony” — a process known to introduce errors and misleading information. Criminal background check service Checkr claims to “[a]utomatically standardize charge data” using a machine-learning classifier to “quickly categorize criminal charges, making charge language clearer and reducing the amount of time spent on manual review.”

Tenant screening companies design their reports to prioritize and highlight certain information for landlords to pay attention to in their decision-making, often emphasizing negative information (or interpreting ambiguous information as “derogatory”). Some reports include a summary at the top, created wholly by the tenant screening service, that includes phrases like “eviction record found” or “negative tradelines,” indicating derogatory information. For example, Turbo Tenant’s sample report includes a credit “profile summary” that includes a category for “derogatory items” and indicates one “negative tradeline.” Scrolling further down the report reveals that the “negative tradeline” is $323 past due on a student loan. Some tenant screening reports will only provide summaries or recommendations to landlords and omit the underlying details of records found.

E. Scoring and making eligibility determinations

Many tenant screening reports include features that are intended to communicate to a landlord whether they should accept, reject, or in some cases conditionally accept (e.g., with a higher security deposit) a renter. These features effectively function as eligibility determinations. Some reports include a three-digit score that resembles a credit score but does not use traditional credit scoring formulas. As is common with traditional credit scores, reports often include a score range, with some indication (like a color gradient from red to green) of what is considered a “good” or “bad” score. Some establish a minimum score below which they recommend rejecting a potential renter.

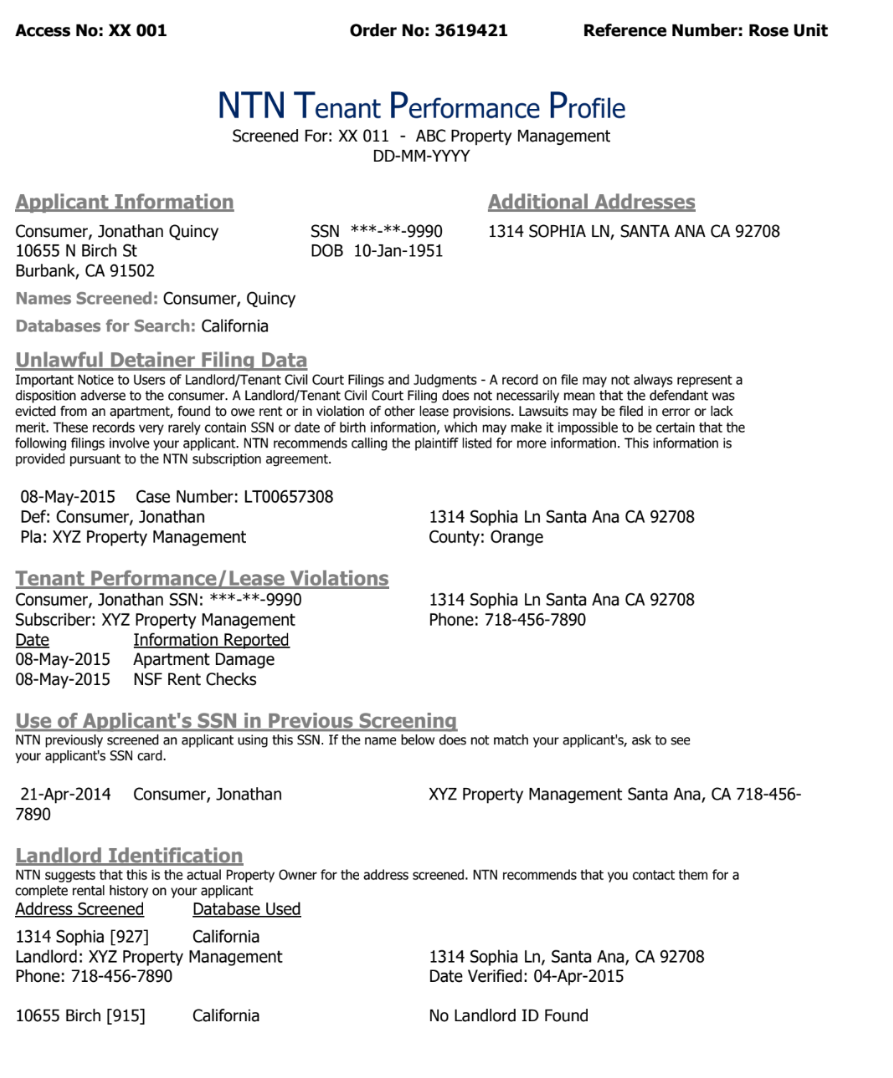

Some reports declare outright that an applicant is eligible or ineligible, or recommend that the landlord accept or reject the applicant. For example, tenant screening company National Tenant Network (NTN)’s sample report includes red, bolded font that says “Does Not Meet Criteria.” In Connecticut Fair Housing Center v. CoreLogic, CoreLogic sent the property manager a screening report indicating that “disqualifying records were found” and “provide[d] no additional information such as the underlying records, the nature of the alleged crime, the date of the offense or the outcome of the case, if any.” In both of these cases, the eligibility determination was apparently triggered by a single record (an arrest record in the case of CoreLogic and an eviction filing in the case of NTN). Some services, like Naborly, prompt landlords to move forward with a rejection (e.g., by clicking a button), and some automatically generate an adverse action notice.

We have very little public information about the algorithms tenant screening companies use to generate scores and recommendations. Some companies suggest or claim that they use machine learning or artificial intelligence (AI). For example, RealPage claims to use “AI Screening” that “leverages the power of AI and machine learning to precisely analyze your applicant pool [and] deliver[] a stronger predictor of future performance and renter behaviors.” But most of the information we can glean from sample reports and other marketing materials suggests that tenant screening companies’ scores and recommendations rely primarily on credit, eviction, and criminal histories, as well as income (or rent-to-income ratios).

Tenant screening scores and other eligibility determinations can automate the process of rejecting tenants due to the records they’ve been matched with. Tenant screening companies often claim that they don’t make rental decisions, but features like scores, recommendations, and automatically generated adverse action notices are designed to encourage landlords to rely in whole or large part on the tenant screening report’s interpretations and conclusions to make a rental decision. For example, SafeRent says that its reports are intended to “eliminate reliance on judgment calls by the leasing staff.” And research suggests that landlords do tend to rely on tenant screening reports and scores to make decisions. In a study of landlord decision-making based on tenant screening reports, Wonyoung So found that landlords tend “ . . . toward automation bias [and] are influenced by the risk assessments and scores presented by tenant screening reports.” The study found that “tenant screening reports that displayed [“mid,” or medium] risk scores were significantly associated with an additional 65.4% decrease in the odds of acceptance . . . .”

F. Rental decision

Landlords often use tenant screening reports to inform their decisions to accept or reject potential renters. Many tenant screening reports functionally come with rental decisions — eligibility determinations (like scores and “disqualifying” records) or built-in actions (like generating an adverse action letter) designed for landlords to rely on when choosing a tenant. Research suggests that landlords tend to be deferential to tenant screening companies’ recommendations. Some landlords have also reported that they tend to reject any tenant with an eviction record, regardless of the disposition of the case.

Rental applicants often receive little information about why they were rejected, even when the law requires it. As the CFPB has reported, many tenants don’t even receive adverse action notices required under the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) — and even those who do are often still left confused about why, exactly, they were rejected.

Some state and local laws limit the information landlords can use to evaluate and reject potential renters, or enforce procedural requirements such as giving rental applicants an opportunity to dispute inaccurate information used to screen them or provide mitigating information to offset negative records. However, these laws usually don’t require landlords to hold the unit open while tenants review and dispute information in their tenant screening reports. Renters — especially those who need housing most urgently — seldom have the time, resources, or incentive to request access to or dispute their reports.

II. Tenant screening reports drive housing insecurity and discrimination by entrenching criminal, credit, and eviction histories as universal barriers to housing.

A. Tenant screening companies primarily repackage eviction, criminal, and credit histories.

Tenant screening companies’ core function is to compile records from public and private databases and repackage them into consumer reports. They often purchase access to databases compiled by third-party data brokers and some may maintain their own databases.

Some tenant screening companies try to set themselves apart from others in the market by highlighting different features (sometimes marketed as “predictive”), such as proprietary scores that indicate an applicant’s likelihood of completing a successful tenancy, or assessing the property’s “suitability” for the applicant’s needs.

However, publicly available information and tenants’ experiences suggest that tenant screening reports and scores still rely primarily on three types of information: (1) credit and financial histories, including income and credit scores and reports; (2) criminal histories; and (3) rental histories — especially eviction records, but also sometimes rental debt reports and other data about previous tenancies, such as their length. Tenant screening companies’ marketing materials and sample reports suggest that these are the primary — if not the only — inputs into their tenant screening scores and other eligibility determinations. For example, SafeRent tells landlords that it uses “key rental data” to identify “tenants who are more likely to pay rent on time, treat the property with care, and stay for longer periods of time.” The “key rental data” SafeRent lists on its website consists of credit history, rental history, and rent-to-income ratio.

Tenant screening companies use their marketing materials, including blog posts and articles, to emphasize the importance of using credit, criminal, and eviction histories to evaluate (and in some cases screen out) renters. For example, TransUnion has published dozens of blog posts telling landlords about the importance of choosing tenants who have no eviction history, a good credit score, a clean criminal background, income that is three times the monthly rent, and a “stable employment history” with no “significant gaps.”

As the following sections will discuss further, eviction, criminal, and credit histories are artifacts of discrimination that should not be used to make housing decisions. People of color, people with disabilities, and people with lower incomes are disproportionately “marked” by these records because of structural racism, structural violence, and organized abandonment. These records are also notoriously inaccurate, and even when they don’t contain errors, they don’t indicate a renter’s ability to pay rent or uphold a lease agreement.

Tenant screening companies’ business model and rhetoric have helped entrench the idea that people with a criminal or eviction record or negative credit history don’t deserve stable, dignified housing, and don’t deserve to choose where they live. This narrative, and the tenant screening industry that upholds it, continue to deepen racial and other forms of housing discrimination, undermining policies and funding aimed at expanding fair housing access.

The following subsections more specifically address the uses of — and problems with — these records in tenant screening.

1. Credit reports and scores

TransUnion tells landlords that “[a] credit score may be one of the most important criteria when evaluating an applicant’s ability and willingness to pay their rent on time.” Some tenant screening reports include a full traditional credit report from a national credit bureau, and some include only certain elements of credit history, like credit scores, collections, or accounts with past due amounts. Relying on credit scores to screen tenants is a form of digital redlining that reproduces racist, classist, and ableist barriers to housing, and locks people out even when they have the income to pay rent.

Credit reports and scores “reflect stunning racial disparities,” as well as disparities based on disability, income, immigration status, gender, and LGBTQ+ identity. The distribution of credit scores by neighborhood, in particular, demonstrates how credit-based tenant screening acts as a form of digital redlining. An Urban Institute survey of financial health in 60 major cities found that, of the 60 cities, 38 had “differences in median credit scores of 100 points or more between predominantly white and nonwhite areas. Nationally, the difference in median credit score is nearly 80 points . . . . Predominantly non-white areas in more than 50 of the 60 cities ha[d] below-prime median credit scores[,]” while “predominantly white areas in only 4 of the 60 cities ha[d] below-prime median credit scores.”

These disparities are caused by social and economic structures like the lack of a financial safety net, the increasing gap between wages and cost of living, the unaffordability of basic needs like healthcare and housing, the historic exclusion of minority groups from wealth-building economic opportunities like home ownership, and the predatory lending practices that feed off of these dynamics. The credit system itself perpetuates these disparities. Abbye Atkinson and other scholars have observed that “credit provides a channel for wealth to leave economically vulnerable communities and travel upward toward the more affluent.” Credit-based tenant screening deepens disparities in access to credit and, more broadly, exacerbates wealth inequality by locking people with lower credit scores out of neighborhoods with better housing conditions, and pushing them further into social and economic precarity.

Credit reports and scores are also frequently inaccurate. A study conducted by the FTC in 2012 found that at least one in five consumers had errors in their credit reports and 13% had errors that affected their credit scores. More recently, Consumer Reports conducted a survey using almost 6,000 credit reports and found that over 30% had at least one error. Errors vary in severity and can include incorrect identifying information such as a name or address, incorrectly reported delinquent accounts, or duplicative listings of debt. At best, these errors can be an inconvenience to consumers that require significant time and energy to fix. At worst, these errors can negatively affect one’s credit and potential life opportunities, including access to housing, which is especially detrimental for marginalized communities with already limited access to credit.

Even when they don’t contain reporting errors, credit reports and scores are unreliable and inappropriate for use in rental housing decisions. As NCLC and other consumer advocates have argued, landlords (and tenant screening companies) “should not rely on credit reports and scores for many reasons.”

First, credit reports and scores are not intended to gauge whether someone will be a good tenant. Credit scores are designed to predict the likelihood that a borrower will become 90 days late on a credit obligation—not rent, which is a different sort of obligation. What’s more, credit reports tell a story about past ability to pay in particular instances, not current ability to pay rent, which is a high-priority bill that families pay before all others. A prospective tenant could show their current ability to pay with paystubs, tax returns, W-2s, and bank statements. . . . [T]here are no quantitative or scientific studies showing that credit reports and scores accurately predict a successful tenancy. Landlords appear to be using credit checks as a result of successful marketing by the credit bureaus or untested assumptions about predictiveness.

Moreover, “[b]ecause tenants recognize the importance of paying their rent, rental payments are paid on-time more than many other kinds of bill, including credit card bills.”

Credit histories are even more irrelevant for renters with housing subsidies. Housing subsidies such as Section 8 vouchers guarantee that a landlord will get a monthly rent payment, and can only be used to pay rent. Yet many voucher holders — who unsurprisingly tend to have lower credit scores — are screened out of housing they can demonstrably afford. As a result, many housing subsidies go unused, and people who need housing most — who wait on voucher waiting lists for months or years before finally getting one — remain locked out of actual housing opportunities. DC acknowledged and sought to partially address this problem in a recent law that prohibits landlords from considering voucher holders’ rental or credit history from before they obtained their voucher. A recent lawsuit against SafeRent alleges that its tenant screening scores have unjustifiable disparate impacts based on race under the Fair Housing Act, because the scores take credit history into account but don’t give tenants credit for having income in the form of a housing subsidy.

2. Criminal records

Advocates, researchers, federal agencies, and some legislative bodies have recognized that criminal record screening perpetuates racial disparities and lacks predictive value, but tenant screening companies continue to emphasize the importance of criminal background checks to “help property owners steer clear of problem renters.” Research suggests that landlords tend to reject tenants who have a criminal record on their tenant screening report. A growing number of state and local laws have sought to limit or prohibit criminal record screening for housing, although the 9th Circuit recently struck down Seattle’s ban on inquiring into applicants’ criminal history on First Amendment grounds, meaning landlords are allowed to conduct criminal background checks even if they aren’t supposed to use the information.

It is well established that criminal record screening perpetuates racial and other forms of injustice. Criminal record screening extends the oppressive power of the criminal legal system by ensuring that contact with the system leads to the denial of basic survival needs like housing and employment, leaving people in a perpetual state of financial and social precarity, which in turn exposes them to further criminalization. Criminal record screening also fundamentally undermines fair housing laws by guaranteeing inequitable access to housing based on race and ethnicity, national origin, disability, sexual orientation and gender identity, and familial status.

Criminal record screening for housing is also a vestige of the “War on Drugs,” when lawmakers passed exclusionary requirements for federally subsidized housing. Since then, comprehensive criminal record screening for all types of housing has been cemented as the norm, propping up a vast and exploitative industry that profits from collecting, buying, and reselling criminal court records. Tenant screening companies are a subset of this industry (tenant screeners are often subsidiaries of or have partnerships with large data brokers), and have a deep financial interest in perpetuating it. Tenant screening companies peddle the baseless idea that landlords must do criminal background checks to protect their neighbors’ or other tenants’ safety.

Criminal records are significantly prone to errors. Errors begin at the source when law enforcement agencies and courts fail to update arrest records or charges with information about the outcome of a case (or fail to do so in a timely manner). Furthermore, when criminal record data is purchased by third-party data brokers or maintained by tenant screening companies themselves, it may be even less likely to be complete or updated for accuracy. Tenant screening companies will also automatically sort criminal records under more simplified labels that can obscure the outcome or context of the case. As a result, charges and offenses can be misclassified (for example, reporting a misdemeanor as a felony). Additionally, it is not uncommon for tenant screening companies to incorrectly — and illegally — report criminal records that have been sealed, expunged, or are older than the FCRA allows. Combined with inaccuracies that stem from sloppy matching practices, reporting criminal records on tenant screening reports is not a reliable practice.

As HUD has acknowledged in its guidance, “criminal history is not a good predictor of housing success.” Criminal records indicate nothing about a renter’s ability to pay rent or otherwise uphold their lease agreement. There is no evidence that criminal records have any predictive value. Some landlords and tenant screening companies use references to “recidivism” to justify their criminal record screening policies; however, recidivism studies are highly problematic and inherently reliant on data created by the criminal legal system itself to establish the system’s validity. As the Shriver Center on Poverty Law and other advocates have pointed out, recidivism statistics “fail to account for the impact of critical supports, such as access to affordable housing. . . . [R]ecidivism rates are a more appropriate measure of the success (or lack thereof) of the prison system than of individuals themselves.”

3. Eviction records

Tenant screening companies have helped entrench eviction records as overwhelming barriers to housing. As with criminal records, data brokers collect eviction records from public court databases, often as soon as landlords file them. Landlords often reject applicants on the basis of any eviction record, including filings, dismissals, and judgments in favor of the tenant. But tenant screening companies mislead landlords about what eviction records represent. Eviction histories are not reliable indicators of tenants’ behavior or ability to pay rent, and they are products of an unjust, racist, anti-tenant housing system. Using them to screen renters deepens housing insecurity, discrimination, and conditions of poverty.

Tenant screening companies use fear mongering to sell landlords on the importance of screening out tenants with eviction records. They claim that eviction is an expensive and difficult process that landlords want to avoid at all costs. However, at a systemic level, eviction is a tool that larger landlords use habitually to exert control over their tenants and extract the maximum possible rents and fees for their units.

Eviction records reflect “striking racial disparit[ies].” As Eviction Lab has found, the rates of eviction and eviction filings are “ . . . on average, significantly higher for Black renters than white renters.” In many cities, evictions are concentrated in low-income Black and Latine neighborhoods. Black and Latine women also face higher eviction rates than men. Researchers speculate that these gender disparities could be due to Black and Latine mothers facing severe financial strain, housing discrimination based on their familial status, low wages, and gender-motivated power imbalances with their landlords. Black and Latine renters are also more likely to be serially evicted, meaning that landlords file multiple repeated evictions against them at the same address. Evictions can also disproportionately burden people with disabilities. For example, some localities have nuisance laws that encourage or require landlords to evict renters for behavior like making a certain number of 911 calls, even if they need emergency medical services.

HUD’s Title VI guidance for subsidized housing providers notes that screening criteria, including eviction histories, “may operate unjustifiably to exclude individuals based on their race, color, or national origin,” and that negative records should not trigger an automatic denial of tenancy. Given the racist distribution of eviction filings, their use in tenant screening is unjustifiable and can only deepen racial injustice in access to housing.

Much like criminal records, eviction records are very prone to errors. A 2020 study found that on average, 22% of eviction records contained ambiguous information on how a case was resolved or falsely represented a tenant’s eviction history. Common errors include missing and inaccurate case dispositions that can make it look like someone was evicted even if their case was dismissed or they reached a settlement. Eviction records are also subject to the same types of matching errors as criminal records.

Even when eviction records don’t contain errors, they are unreliable for determining whether someone can pay their rent or otherwise uphold their lease agreement. The vast majority of eviction records do not represent any court finding that the tenant violated their lease agreement. Many eviction records that appear on tenant screening reports are just filings, meaning they only represent that a landlord filed for eviction. Many eviction filings get dismissed because the landlord had no legal basis to evict the tenant or because the tenant paid the rent they owed. Most jurisdictions allow landlords to file for eviction for reasons that involve no fault (or without “good cause”), such as the landlord deciding to remove their property from the rental market. In King County, WA, no-cause terminations were the second most common basis for evictions in 2019.

Eviction records do not represent tenants’ behavior; they represent the vast power imbalance between landlords and tenants. It costs relatively little to file an eviction action — as little as $15 — which helps explain the high rate of eviction filings compared to judgments. The threat of eviction allows landlords to leverage the state’s police power to collect on missing rent, to avoid making repairs, or to push current tenants out and raise rents without running afoul of rent control restrictions. When landlords threaten to evict, tenants often leave voluntarily to avoid a record that will imperil their future housing opportunities.

Recently, the CEO of TransUnion testified before Congress that TransUnion plans to stop reporting on eviction records except for the “final outcomes of eviction proceedings.” This change would improve upon the status quo if adopted by all CRAs. But eviction judgments still belie a court process that is heavily anti-renter. Many tenants lose their cases because of a lack of notice about how and when to appear in court, the cost and time required to defend against an eviction, a lack of representation (many places still do not have a right to counsel in eviction court), and the “one-sided, factory-like process in favor of landlords.”

Even when eviction records reflect missed rent payments, they don’t necessarily reflect renters’ current ability to pay rent. Temporary financial hardship should not sentence people to be locked out of future housing. Eviction histories are especially irrelevant for renters who have housing subsidies — the very thing intended to help people who are struggling to pay rent — because housing vouchers guarantee that landlords will get paid.

Landlords almost always ask for prospective tenants’ current income information on rental applications, which should obviate the need to use unreliable eviction records as a basis for predicting whether someone can pay rent. Yet, tenants, especially those with housing vouchers, are often screened out of housing they can afford because of their eviction histories.

Finally, the vast majority of evictions are filed for alleged nonpayment of rent, yet tenant screening companies sometimes claim that eviction records indicate other types of risk, such as the risk that a tenant will damage the property. For example, AAA Credit Screening Services encourages landlords to check eviction records to reduce landlords’ risk of legal responsibility for tenants’ criminal activities. TransUnion, one of the largest consumer credit reporting agencies, advises landlords that checking eviction histories protects against “lost rent, property repairs, and eviction-related expenses.”

Eviction is a consequence of a housing system that is unjust, unaffordable for too many people, and prioritizes the interests of investors and profits over providing housing for people. The records produced by this system represent deep racial, economic, and social inequities. Especially given the lack of reliable information about tenants contained in eviction records, using them to make housing decisions is unjustifiable.

B. Tenant screening companies effectively make housing decisions and encourage landlords to rely on them.

Tenant screening companies often try to disclaim any responsibility for making housing decisions, or even for the accuracy or predictive value of the information they present to landlords. For example, RealPage’s terms of service disclaim any liability for the accuracy of the information it provides or its “fitness for a particular purpose.”

But tenant screening companies intentionally design their reports, services, and marketing to encourage landlords to rely on tenant screening reports’ interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations. In doing so, tenant screening companies contribute significantly to, and in many cases functionally make, decisions about whether an applicant is accepted or rejected. Some of these services are designed to streamline or significantly automate the process of rejecting applicants based on certain criteria in their backgrounds. For example, CoreLogic automatically generated an adverse action letter for WinnResidential to send to Mikhail Arroyo, which WinnResidential passed along without ever receiving or reviewing Arroyo’s records. Naborly’s sample report shows thumbs up and thumbs down buttons for landlords to accept or reject an applicant.

In their marketing language — which includes articles purporting to give legal compliance advice — tenant screening companies tell landlords that using their services is the best way to “ . . . identify whether an applicant is likely to be a good tenant or a problem tenant . . . ,” and to comply with relevant laws. They characterize their reports as providing “comprehensive” information and predictions that landlords can rely on “ . . . to make sound rental decisions.”

Features such as three-digit scores, risk predictions, and other eligibility determinations are designed to point landlords clearly toward a decision. For example, NTN’s DecisionPoint product scores applicants from 0 to 100, indicating whether they meet or fall short of specific criteria. Some tenant screening services provide outright conclusions about whether a tenant is qualified.

Evidence from Wonyoung’s So’s study on landlords’ use of tenant screening reports suggests that landlords do tend to follow tenant screening companies’ recommendations. A study by Anna Roesti that included interviews with landlords and tenant screening companies included this quote: “[Landlords are] saying ‘We like using SafeRent because it tells us red, yellow, green lights and our people don’t have to think. We don’t want them to think.’”

Tenant screening companies automate housing discrimination by using eviction, credit, and criminal histories as a basis for making conclusions about tenants’ eligibility, and producing “passing” or “failing” scores and other features intended to automate the process of rejecting tenants.

III. Tenant screening reports undermine policies and funding aimed at improving access to housing.

Federal, state, and local governments — as well as community organizations, tenant organizers, and direct service providers — spend significant money and resources to improve equitable access to housing, make housing more affordable, and enforce fair housing laws. During the COVID-19 pandemic, federal and local funding for housing subsidies increased, and more vouchers were distributed. HUD is currently focusing energy and resources on revising the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule to strengthen fair housing obligations.

But the efficacy of these efforts hinges on people actually being able to get housing. Screening out tenants based on background checks undermines policies and funding aimed at improving access to fair housing, especially funding for vouchers. Stories abound of people who wait for years for a housing voucher only to find that no landlord will accept them after a background check. Our systems for distributing housing must be transformed, but as long as we are relying on vouchers as a way to provide “affordable” housing, the federal government must recognize that prevailing tenant screening practices and tools are completely incompatible with expanding housing access.

IV. "Objectivity" and standardization in tenant screening do not protect against discrimination.

The RFI asks whether “objectivity in the tenant selection process” should be “a regulatory goal.” The RFI does not define what it means by “objectivity,” but in context, it appears to refer to limiting landlords’ subjective discretion in the tenant screening process. Limiting landlords’ discretion is a reasonable policy goal; however, it’s important to acknowledge that removing landlord discretion will not make the tenant screening process unbiased, since tenant screening is informed by and takes advantage of structurally discriminatory systems and records, and political choices about who deserves housing.

The federal government could limit the information landlords and tenant screening companies can use to screen tenants. But establishing a standardized, and uniformly applied, set of tenant screening criteria still will not address the underlying housing discrimination problem: using background checks, including credit, eviction, and criminal histories, to screen renters will inevitably have disparate impacts based on race, disability, and other protected classes.

HUD’s Fair Housing Act guidance highlights the tension between standardizing the tenant screening process and preventing housing discrimination. For example, in its criminal record screening guidance, HUD warns against “blanket” criminal record screening policies, and states that “policies or practices that fail to consider the nature, severity, and recency of an individual’s conduct are unlikely to be necessary to serve a substantial, legitimate, nondiscriminatory interest.” Following this guidance, some state and local fair chance housing laws require landlords to engage in an “individualized assessment” or disparate impact-style analysis before rejecting tenants based on criminal records (and in some cases other factors).

HUD’s guidance has helped raise landlords’ and tenant screening companies’ consciousness about the need to re-examine their practices and assumptions with respect to criminal records. Evidence suggests that landlords tend to be more willing to overlook, or consider mitigating information about, criminal records than they are for eviction records. The FTC, CFPB, and HUD can use their authority to build a similar level of understanding around the problems with relying on eviction and credit histories.

Federal agencies should avoid establishing a set of criteria that they deem “fair,” “objective,” or legally justifiable for screening out renters. Doing so could set a dehumanizing precedent that renters with certain records in their backgrounds — disproportionately Black, Latine, disabled, and low-income renters — don’t deserve dignified housing, or to choose where they live. It could also undermine future state and local efforts to ban tenant screening based on certain criteria, like criminal records and credit histories. The burden should always be on housing providers to rigorously justify any criteria or information they use to deny someone housing.

V. Existing remedies leave large gaps in renter protections and enforcement.

The coverage and enforcement of existing renter protections are limited in ways that leave gaps for federal agencies to fill. Challenging tenant screening outcomes often requires information, time, and resources that renters — and often legal service providers — don’t have access to. The whole federal government must work to fill these gaps, but the FTC is particularly well positioned to enforce against tenant screening companies’ unfair and deceptive practices, and ensure that renters are preemptively protected from discriminatory tenant screening reports.

A. The Fair Credit Reporting Act

The primary federal regulatory authority over the creation and use of tenant screening reports stems from the FCRA. The FCRA regulates the purposes for which consumer reports (including tenant screening reports) can be used; how long certain information — including criminal and eviction records — can be reported; requirements for dispute investigation processes and adverse action notices; and reasonable procedures for assuring maximum possible accuracy. Despite these provisions, the FCRA is significantly limited in terms of effective protections for tenants and enforcement processes.

Though the FCRA requires CRAs to “follow reasonable procedures to assure maximum possible accuracy,” it falls short in defining what reasonable procedures are to look like. A few pieces of agency guidance delineate especially abhorrent practices that violate the FCRA, such as name-only matching. While useful, existing guidance is not sufficient to deter ongoing practices that result in inaccuracies (as illustrated by the upward trend in consumer complaints about such inaccuracies). Accuracy requirements must be more specific to effectively protect consumers.

Moreover, current FCRA enforcement is insufficient to ensure that consumer reports contain accurate and up-to-date information. Under the FCRA, CRAs are not allowed to report non-conviction criminal information beyond seven years, yet obsolete information is still reported. This practice ensures that a criminal record follows consumers far beyond what is legally allowed and results in the denial of housing. The reporting of obsolete information is an ongoing problem for applicants which illustrates that existing reporting requirements are not adequately enforced to ensure accuracy and fairness for consumers.

When applicants are denied housing, they have the right to know, and this notice plays an especially important role in identifying denials based on inaccurate or obsolete information. Under the FCRA, landlords are required to provide applicants with an adverse action notice if they are rejected or conditionally accepted. Adverse action notices are what inform applicants of their rights to see their tenant screening reports and dispute any information on them, yet landlords often do not provide these notices. This means that despite the FCRA’s requirements, applicants are often unaware of the reason behind a denial — including inaccuracies that contributed to that decision — and cannot address the issue in time to be accepted for a unit. This requirement is one of the only forms of redress available to applicants, yet the lack of adequate enforcement means that it is often not available at all.

Even when an applicant is made aware of inaccuracies, the existing process for addressing inaccurate information in a consumer report fails to protect tenants. The FCRA requires that CRAs investigate consumer disputes within 30 days, but that is not quick enough for consumers who are likely to be denied housing in that time, assuming a CRA even responds. It is not uncommon for CRAS to violate consumers’ rights to a timely investigation, which prolongs the time it takes to get housing. The CFPB has also found that the national credit bureaus address the concerns of consumers in less than 2% of covered complaints. Even in the rare case that consumers are able to get relief, the same errors may show up later on different tenant screening reports. These problems illustrate that the existing framework for ensuring accuracy and subsequent enforcement actions is inadequate to protect consumers.

B. State and local fair chance housing laws

Many states and localities have passed critical protections, often called “fair chance housing” (FCH) laws, to mitigate the harms of tenant screening. FCH laws usually do some combination of:

limiting the criteria, information, and records landlords can use to screen tenants. For example, some FCH laws prohibit landlords from using a credit score and/or an eviction that did not result in a judgment in favor of the landlord, and many restrict criminal background checks.

requiring landlords to notify potential rental applicants of the criteria and information — and sometimes the tenant screening service — they’ll use to screen applicants;

requiring landlords to tell applicants why they were rejected and to give applicants an opportunity to access the information/reports used to screen them and correct inaccurate information or provide mitigating information. Some laws expressly require landlords to consider the mitigating information or corrections;

requiring landlords to conduct an individualized assessment, rather than use a blanket rejection policy, if they use certain information to screen tenants;

requiring landlords to consider applicants on a first-in-line basis and accept the first qualified applicant; and

limiting application fees or requiring landlords to disclose how they use application fees.

FCH laws provide critical tenant protections that did not exist before, but they leave several gaps that federal agencies can help fill. Most importantly, FCH laws today generally only cover housing providers, not tenant screening companies. The result is that a landlord may be prohibited from considering an arrest record or eviction filing, but may still see that record on a tenant screening report, or it may be incorporated into a tenant screening score unbeknownst to the landlord. The efficacy of these laws thus depends on landlords’ compliance — i.e., ignoring information on a tenant screening report — and on renters’ and tenant advocates’ discovery and notification of violations. Establishing a causal connection between prohibited uses of tenant screening reports and denial of housing, however, is especially difficult when landlords can see restricted criteria and use pretextual reasons to reject renters. This problem has been made worse by the recent decision in Yim v. Seattle, in which the 9th Circuit held that prohibiting landlords from “inquiring into” certain information in a tenant’s background violates landlords’ First Amendment rights. As a result, local ordinances can prohibit landlords from using certain criteria to screen tenants, but landlords must still be allowed to seek out such information and receive it in a tenant screening report. The FTC, CFPB, and HUD must fill this gap by restricting tenant screening companies’ ability to report information like criminal and eviction records.

FCH laws may be difficult to enforce for the reasons explained above, and because local agencies, tenant advocates, and renters themselves have limited capacity to discover and remedy violations. Local enforcement agencies often rely on renters to submit complaints about violations rather than proactively monitoring tenant screening practices. This often means that when an applicant is rejected, they must take the time to request a copy of their report, provide mitigating information, and/or submit a complaint or seek out legal assistance to do so. Renters — especially low-income renters and renters with discredited backgrounds — likely lack the time and resources to take these steps while also searching for housing. Most applicants must simply move on to the next application to meet their immediate need for housing. Renters must be preemptively protected from screening based on unfair and discriminatory criteria, not forced to constantly explain their histories or try to convince landlords to give them a chance.

When landlords violate FCH laws, the laws usually do not provide the only remedy that really matters: housing. They generally don’t require landlords to hold a unit open for long enough to give applicants reasonable time to request their report and provide mitigating information. Philadelphia’s Renters’ Access Act is a rare exception, requiring landlords with five or more units who incorrectly screen out tenants to offer those tenants the next available unit. In many cases, by the time an applicant does this, the landlord will have already rented to someone else. Without housing as a remedy, renters have little incentive to pursue their rights under FCH laws.

However, some FCH laws include good examples of protections from discriminatory screening that federal agencies should build on. For example, DC prohibits landlords from screening voucher holders based on credit or rental histories from before they received their voucher. In fact, the law incorporates this type of screening into the definition of voucher discrimination under DC’s Human Rights Act. Some particularly strong FCH laws, such as Seattle’s, ban virtually all criminal record screening, setting a standard that other localities and the federal government should follow.

C. Sealing

Some states and DC have passed laws to seal some eviction records and/or to strengthen existing criminal record sealing regimes. Sealing — especially laws that seal eviction records immediately at the point of filing, as in California — is a critical renter protection because it prevents data brokers from accessing some records and including them in tenant screening reports. The White House set an important precedent in its Blueprint for a Renters Bill of Rights when it stated that “eviction case filings should immediately be sealed, including in cases of nonpayment or rent, thereby reducing the chance for people to be locked out of future housing opportunities without a chance to defend themselves.”

However, sealing is necessarily limited. For example, laws that seal pending eviction cases must provide some ability for people to access sealed records for purposes like eviction defense, research, and news reporting. It would not be legal or desirable to seal pending cases so tightly as to assure that no one could ever access them, but data brokers may try to exploit any vulnerabilities or exceptions in sealing laws. Moreover, criminal record sealing laws usually only apply to concluded cases and provide little or no protection to people with open cases. Sealing laws vary between states and localities, so a rental applicant who moves to a state that seals eviction records may still face barriers to housing from an eviction in a different state. Finally, sealing only covers court records and provides no protection against the use of credit reports and other private-sector information. State and local sealing laws must be shored up by federal restrictions on tenant screening companies’ reporting of eviction and other records.

D. Fair Housing Act enforcement

Fair Housing Act enforcement against unfair and anti-renter screening practices could be much more robust. HUD’s strongest engagement on tenant screening has been issuing guidance and announcing its intent to do rulemaking on criminal background checks for rental housing. Through its guidance, HUD has set a relatively strong precedent that criminal record screening is likely to cause discriminatory effects under the Fair Housing Act, that blanket criminal record screening policies and the use of arrest records cannot be justified under the Act, and that any criminal records used in tenant screening must indicate a “demonstrable risk.”

HUD could (and should) extend similar reasoning to eviction and credit histories. HUD and the Department of Justice (DOJ) have acknowledged that “credit screening may, in certain circumstances, have an unjustified discriminatory effect, and therefore be unlawful.” In Title VI guidance to subsidized housing providers, HUD warned that

Screening criteria, such as those related to criminal records, credit, and rental history, may operate unjustifiably to exclude individuals based on their race, color, or national origin. . . . In evaluating rental history, housing providers should consider the accuracy, nature, relevance, and recency of negative information rather than having any negative information trigger an automatic denial. For example, records from eviction or related cases in which the tenant prevailed or that were settled without either party admitting fault do not necessarily demonstrate a poor tenant history.

However, HUD has not yet provided comprehensive Fair Housing Act guidance on eviction and credit histories or other tenant screening practices.

HUD should work to fill these gaps in Fair Housing Act enforcement, but the FTC and CFPB also collectively have the authority and responsibility to enforce against the unfair, deceptive, inaccurate, and discriminatory use of background screening. The FTC and CFPB are well positioned to address these technologies and to contribute their expertise and information to HUD’s development of guidance and enforcement priorities.

Renters also need the FTC and CFPB to enforce against a broader set of consumer harms that may exceed the scope of discrimination covered under the Fair Housing Act, or where disparate impacts under the Fair Housing Act may be difficult to demonstrate. For example, the FTC can enforce against deceptive misrepresentations in tenant screening reports that lead to denials of housing without having to make a statistical showing of disparate impact. While tenant screening companies are covered under the Fair Housing Act, the FTC may be able to enforce against a broader range of tenant screening companies’ unfair and deceptive practices, like encouraging landlords to pass excessive fees or rents onto tenants.

VI. Recommendations

A. The FTC should use its authority under Section 5 of the FTC Act to enforce against unfair and deceptive tenant screening practices. The FTC should prioritize enforcing against tenant screening practices that are likely to have discriminatory impacts.

Existing laws and enforcement have left large gaps in protections for renters, which the FTC is well positioned to fill using its authority under Section 5 of the FTC Act. As explained in a 2021 letter to the FTC from a coalition led by the Shriver Center on Poverty Law:

Regulation of both tenant screening companies and the tenant screening practices of landlords is well within the FTC’s established bailiwick. . . . [T]he FTC has already addressed tenant screening practices in guidance directed to both landlords and screening companies. There is, indeed, ample precedent that discrimination, in the housing context and otherwise, also violates consumer protection laws, and consumer protection agencies enforce specific prophylactic measures to guard against such discrimination in other contexts.

As discussed below, the FTC should use its Section 5 authority to enforce against unfair and deceptive tenant screening practices — especially those that are likely to result in housing discrimination. The FTC should also consider issuing guidance clarifying that the practices discussed in this comment are unfair and/or deceptive.

1. Unfair tenant screening practices

An unfair practice is defined as one that “causes or is likely to cause substantial injury to consumers which is not reasonably avoidable by consumers themselves and not outweighed by countervailing benefits to consumers or to competition.” The FTC’s authority is purposefully broad and allows the FTC to prevent unfair business practices by both landlords and corporations.

i. Tenant screening causes substantial injury

Tenant screening causes substantial injury to renters, especially when it results in the denial of housing or less favorable terms and conditions, such as additional fees, on the basis of a protected class. Tenant screening practices can also cause substantial injury by deterring renters from applying to housing they can afford, increasing the time and financial burden of searching and applying for housing, increasing the cost of housing, and chilling renters from complaining about poor housing conditions or defending themselves against evictions.

Substantial injury is not trivial or speculative but rather usually involves monetary harm or significant risks to consumers’ health and safety. Access to stable housing is critical to health outcomes as those without housing stability have poorer mental and physical health and increased mortality.

Applicants can suffer monetary harm as a result of the screening process. The average cost of a rental application, including a tenant screening report, is between $40 and $59, though a single application can be more than $100. As a result, if an applicant is consistently denied housing, they can pay hundreds of dollars in fees for applications and tenant screening reports before finding a landlord willing to accept them. For applicants with “discrediting background records” the housing search process can be particularly long and time consuming, forcing applicants to miss work and incur further economic losses. Many applicants lose the value of their long-awaited housing vouchers because they cannot find a landlord who will accept them before their voucher expires. The collateral consequences of an eviction record make it easier for landlords to displace tenants without going through a court process, in what is known as “informal eviction.” Tenants will often leave voluntarily rather than defending themselves to avoid getting an eviction record.

Furthermore, tenant screening relies on inherently discriminatory information such as criminal, credit, and eviction history, which disproportionately affects low-income communities, communities of color, and people with disabilities. Tenant screening practices that have a disparate impact based on a protected class are unfair. In FTC v. Passport Automotive Group, the FTC alleged that discriminatory auto loan financing practices constituted unfair practices under Section 5. In a joint statement in the Matter of Napleton Automotive Group, FTC Chair Khan and Commissioner Slaughter wrote that “discrimination based on protected status is a substantial injury.”

ii. Renters cannot reasonably avoid the harms of tenant screening.

Housing is one of the most basic necessities, and most landlords use some form of tenant screening reports, so renters can rarely, if ever, refuse to be screened before accessing housing. Renters often report that they are not informed of screening criteria before applying, so they can’t even make informed decisions about where to apply. The large variety of tenant screening companies and reports in the market means that tenants usually cannot find out what their reports will look like ahead of time. Rental applicants (and landlords themselves) are even less likely to have information about the factors and algorithms tenant screening companies use to produce scores, predictions, and eligibility determinations. Finally, many applicants report never receiving adverse action notices after being screened out of housing.

Renters also cannot avoid being screened based on inaccurate or misleading information, such as outdated records or information on a different person altogether. Even if an applicant becomes aware of inaccurate information, the CFPB has reported that tenant screening companies often ignore complaints. For applicants who do successfully get their reports corrected, the process can take a long time, and generally cannot be resolved before the landlord rents the unit to someone else. The ubiquitous need for housing coupled with opaque algorithms and inaccurate information makes it difficult for consumers to “survey the available alternatives, choose those that are most desirable, and avoid those that are inadequate or unsatisfactory” as anticipated by the FTC.

iii. The harms of tenant screening practices are not outweighed by countervailing benefits to consumers or competition.

In determining whether a practice is not outweighed by countervailing benefits, the FTC must examine whether the practice is “injurious in its net effects.” In their joint statement in Napleton, Chair Khan and Commissioner Slaughter noted that injuries resulting from disparate treatment or impact are not outweighed by countervailing benefits nor do they overcome the costs associated with discrimination.

The alleged benefit of tenant screening is to minimize risk for landlords by selecting tenants who will pay their rent on time and take care of their unit and by helping landlords comply with fair housing requirements and other laws. But most tenant screening reports rely on information — such as criminal, credit, and eviction records — that is inaccurate, has little or no documented value for predicting tenancy outcomes, and reproduces housing discrimination rather than helping landlords avoid it. Importantly, there are less discriminatory alternatives to using these tenant screening reports. Landlords could simply accept the first applicant whose income demonstrates their ability to pay rent.

iv. Examples of unfair tenant screening practices

The FTC has already indicated that tenant screening practices can be unfair or deceptive. The FTC settled with Appfolio over alleged violations of both the Fair Credit Reporting Act and Section 5 of the FTC Act for issuing tenant screening reports that included eviction and non-conviction criminal records older than seven years and information on other consumers. In a dissenting statement, Commissioner Chopra noted that the widespread “shoddy use of criminal records and eviction records” in the background screening industry is both harmful and potentially discriminatory. Failure to provide accurate information is common in the background screening industry and has led to at least two other FTC enforcement actions against screening companies, RealPage and HireRight.

While the FTC and CFPB have actively enforced and issued guidance against inaccurate tenant screening practices, federal enforcement must go beyond addressing inaccuracy to truly protect tenants. Even when tenant screening reports are technically free of errors, they unjustifiably limit access to housing and automate discrimination.

Screening out tenants based on criminal, eviction, and credit histories

As these comments have explained, screening tenants based on criminal, eviction, and credit histories reproduces housing discrimination and unjustifiably limits access to housing. The FTC should enforce against tenant screening companies’ and landlords’ reliance on these records as screening criteria, including their dissemination in tenant screening reports and incorporation into scores and recommendations. Some of the concrete harms of these practices include:

Preventing people from recovering from past financial hardship or incarceration by locking them out of dignified homes, which are essential for mental and physical well-being and economic stability;

Disproportionately denying housing opportunities to people of color (especially Black and Latine people), immigrants, low-income renters including voucher recipients (despite adequate proof of income), people with disabilities, and potentially people with children;

Locking people with housing vouchers out of the rental market and undermining the entire subsidized housing system;

Chilling renters from defending against evictions due to the threat of getting a record that will follow them around, and allowing renters to be forced out of homes where they have legal justification to stay;

Plunging people further into economic and social precarity, and in some cases forcing people into homelessness.

As these comments have discussed, these harms are not reasonably avoidable, and they are not outweighed by any countervailing benefits since the records at issue do not actually indicate tenancy outcomes, were not designed to be used for tenant screening, and are unavoidably inaccurate.

The FTC should refer to the HUD’s criminal record screening guidance as a template for alleging that screening out tenants based on criminal, credit, and eviction histories is unfair. HUD has advised that criminal record screening is likely to result in disparate impacts based on race that often cannot be justified under the Fair Housing Act — at least not without an individualized analysis that the conduct denoted by a conviction record indicates a “demonstrable risk” to safety — because “criminal history is not a good predictor of housing success.” HUD’s disparate impact analysis aligns well with the elements required to allege unfairness. The FTC should also extend this analysis to eviction and credit histories.

Making and disseminating tenant screening reports, scores, and eligibility determinations that encourage landlords to reject housing applicants without an individualized assessment

Tenant screening companies use algorithms to produce scores, risk predictions, and recommendations about tenants’ “eligibility” that collapse any context or nuance in tenants’ backgrounds. These features encourage landlords to apply rigid rules that deny tenants an individualized assessment and an opportunity to provide mitigating information. As a result, these features automate housing discrimination, unjustifiably limit access to housing, and undermine policies and funding aimed at improving fair housing access.

Tenant screening companies have provided little to no information about how they produce their scores and recommendations and have provided no concrete evidence that they can actually predict or improve housing outcomes. Thus, there is no evidence of countervailing benefits from these features.

The FTC is well positioned to address unfair design and use of algorithms and “predictive” technologies. Commissioner Slaughter has stated that “ . . . if an algorithm is used to exclude a consumer from a benefit or an opportunity based on her actual or perceived status in a protected class, such conduct should [] give rise to an unfairness claim.” Therefore, the FTC “ . . . should be aggressive in its use of unfairness [authority] to target [such conduct].”

Other examples of unfair practices include:

Using rental application fees to extract a profit from applicants;

Failing to refund rental application fees when the landlords fails to evaluate the application;

Failure to take measures to guard against discrimination, such as searching for less discriminatory alternatives

2. Deceptive tenant screening practices

Tenant screening companies regularly engage in at least two types of deceptive practices: (1) peddling inaccurate and misleading information in tenant screening reports for landlords to rely upon when making housing decisions; and (2) making false marketing claims about their ability to predict tenancy outcomes.

A deceptive practice is defined as a material representation, omission, or practice that is likely to mislead a consumer acting reasonably in the circumstances. The FTC determines materiality by examining whether the practice would “affect the consumer’s conduct or decision with regard to the product or service.” “Information has been found material where it concerns the purpose, safety, efficacy, or cost of the product or service. Information is also likely to be material if it concerns durability, performance, warranties, or quality.” Furthermore, even when accurate information is provided in fine print, it may not be enough to offset misrepresentations in a headline.

Inaccurate information and misleading representations in tenant screening reports

Tenant screening reports are designed and marketed for landlords to rely on them when making decisions about whether to accept or reject potential tenants. A reasonable consumer would expect the information contained in tenant screening reports to be reasonably accurate and fit for the purpose of evaluating and choosing tenants. Yet tenant screening companies create misleading representations when they report information that is inaccurate, incomplete, does not belong to the applicant, and/or is otherwise not fit to use to evaluate a potential tenant.

Examples of this type of deception include:

creating reports that contain other consumers’ information (“matching errors”);

falsely attributing negative criminal, credit, or eviction history to an applicant;

attaching false or misleading labels to criminal records (such as labeling misdemeanors as felonies);

misrepresenting the nature of a criminal or eviction case by omitting critical information such as its disposition (e.g., not reporting that it was dismissed); and/or

reporting on eviction filings or arrests, which are mere allegations and cannot be relied upon.