For the past four years, the Chicago Police Department has been working with researchers to build a system for judging which city residents are most likely to be involved in a shooting — either pulling the trigger, or getting shot. The resulting “heat list” — officially called the Strategic Subjects List (SSL) — has, for the most part, been shrouded in secrecy and speculation. What we’ve known is that everyone on the list gets a risk score, reflecting their predicted likelihood of being involved in a shooting.

The list is, to our knowledge, the highest-profile person-based predictive policing system in use across the United States. Perhaps that’s why it has attracted significant press attention — often including overstated comparisons to Minority Report — even though little is known about how it works. Most predictive policing systems fielded by major U.S police departments today are “place-based,” meaning they attempt to forecast when and where future crime may occur. Chicago’s system, by contrast, tries to forecast who will be involved.

For years, advocates have been looking for answers. How many people get high enough risk scores to land “on the list,” receiving special attention from the police? 426? 1,400? 30,000? What happens to the people who are on the list? How do Chicago police actually use the list?

Careful research by the RAND Corporation found that an early version of the program “does not appear to have been successful in reducing gun violence” — a conclusion the police contested. Until now, the public hasn’t had a direct view of what was happening.

Now, thanks to a Chicago Sun-Times FOIA request and legal battle, we have the entire de-identified SSL dataset — the data that went in about each person, and the risk score that came out, but without identifiable information about each individual. At Upturn, we’ve been researching the Strategic Subjects List, as well as other predictive systems within the criminal justice system, for more than a year, so we were eager and ready to dive into this new disclosure.

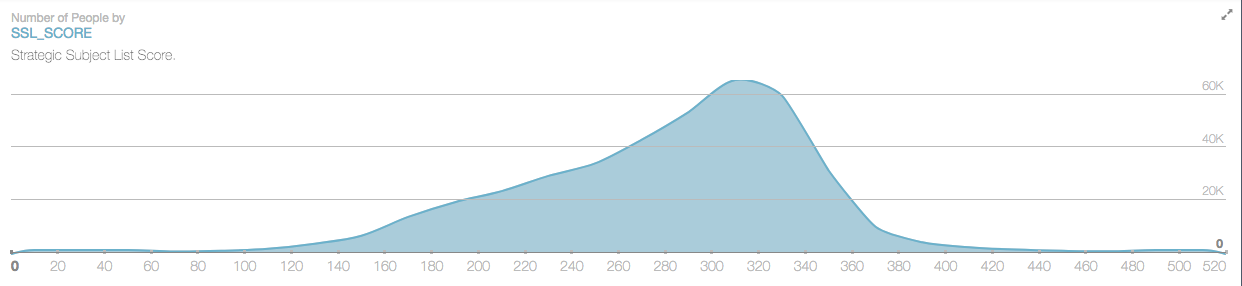

The entire Strategic Subjects List dataset consists of 398,684 individuals. That’s the whole universe from which a smaller, “strategic list” gets culled.

What’s really surprising is that, out of those 398,684 people, 287,404 have scores over 250, the level that CPD says earns them heightened police scrutiny. That’s more than two-thirds of the entire list. Further, it’s not clear how all of these “higher risk” individuals were placed on the SSL in the first instance.

Many people in the data have no obvious markers traditionally associated with “high risk of criminal activity,” and many of that ostensibly lower-risk group nevertheless have scores above the CPD cutoff: 127,513 individuals on the list have never been arrested or shot, but around 90,000 of them are deemed to be at “high risk.”

That’s just one of our findings. Below, we detail all we know about the list, all we’ve learned from this newly released data, and what we still hope to find out.

What is the list?

The Strategic Subjects List is, according to Special Order S09–11, supposed to “rank individuals with a criminal record according to their probability of being involved in a shooting or murder, either as a victim or an offender.” Individuals are ranked on a score between 1 and 500, and the scores are recalculated every day.

In some ways, the idea of a “list” is misleading. Jeff Asher, a crime analyst in New Orleans, noted that it might be “helpful to think of the SSL not as a list but as an algorithm applied to anyone who’s arrested.” In reality, the population that gets sized up is broader than just arrestees. According to the Sun-Times, the “list” released by the CPD includes, at a minimum, anyone who had been arrested or fingerprinted in Chicago between August 1, 2012 and July 31, 2016. But there may also be other ways to end up getting a risk score —unfortunately, that’s not clear from the public record.

What do scores mean?

People at risk of being shot and those likely to threaten others (two overlapping but distinct groups) receive high scores. The scores do not distinguish between a potential victim and potential perpetrator. The CPD says that it will pay closer attention to individuals with a score of 250 or above.

“Like a credit score, the SSL is simply a tool that calculates risk,” according to CPD spokesman Anthony Guglielmi. “Individuals only really come on our radar with scores of 250 and above.” (While the credit score analogy might be the CPD’s attempt to make the SSL seem more approachable to the Sun-Times’ audience, as any financial justice advocate would tell you, credit scoring systems reflect stunning disparities, in large part due to the racial wealth gap and other symptoms of structural discrimination. And here, the outcome of the “scoring system” could have even more troubling life-altering consequences.)

How are scores calculated?

After a lengthy legal dispute between the CPD and the Chicago Sun-Times, the CPD released a de-identified dataset. They did not release the algorithm used to actually calculate the scores — though the Sun-Times and several other parties are now suing the CPD for that. However, the CPD did officially release the variables used to create someone’s score.

Those variables are:

The number of times an individual was a victim of a shooting;

An individual’s age during their most recent arrest;

The number of times an individual was the victim of an aggravated battery or assault;

The number of prior arrests an individual had for violent offenses;

The individual’s number of prior narcotics arrests;

The number of prior arrests an individual had for unlawful use of a weapon;

An individual’s trend in recent criminal activity;

An individual’s gang affiliation.

The social network of individuals — as defined by co-arrests — was previously a core factor in the SSL model. However, this variable is not in the dataset and is apparently no longer used by the CPD to calculate SSL scores.

A recent New York Times analysis worked backward from the data and scores to estimate the formula that assigns the scores. Our own analysis, conducted before the Times piece was published, largely mirrors their findings. We found that the most important factor in an individual’s SSL score was their age: age accounts for roughly 89% of variance in SSL scores. In other words, the score mostly just reflects each person’s age. Other factors, like an individual’s latest weapons arrest or the last time they were a party to violence (meaning they were involved in a shooting or a murder), do significantly contribute to shaping an individual’s score, but less so when compared to an individual’s age.

In other words, the scores, as they stand, do little more than reinforce the “age out of crime” theory — a theory that suggests individuals “grow out” of crime in their 30s. If the SSL — which has cost taxpayers millions of dollars — simply rank-orders younger Chicagoans as riskier and reproduces well-known social science findings, one has to wonder just how “strategic” it really is.

How are scores used?

The CPD says that it will pay closer attention to individuals with an SSL score of 250 or above. But determining what exactly officers do with individuals who have a score of 250 or above is not clear. Further, it’s unclear why 250 was chosen as the threshold. In an editorial just last year, the Chicago Tribune noted that when Superintendent Eddie Johnson attributed the “city’s violence to 1,300 people, he was referring to those with a score on the strategic subject list somewhere in the upper 200s or higher.”

But, as previously mentioned, more than 280,000 individuals have a score of 250 or higher. The CPD is a department of more than 12,000 officers. That makes it one of the largest police departments in the country. But if 280,000 individuals have risk scores that would put them “on [the CPD’s] radar,” one has to wonder: how strategic is the Strategic Subjects List, really?

It may be helpful to imagine you’re a CPD officer beginning your shift. Officers are aware of who on their beat is on the list. According to a RAND report on the SSL, officers were observed discussing highly-ranked individuals during meetings and briefings. But officers were also directed not to include an individual’s score in a police report should they be involved in an arrest. This makes it difficult to track exactly how the police are using the list and to evaluate whether placement on the list influences an officer’s interaction with an individual. At least with respect to earlier versions of the SSL, “commanders were not given specific guidance on what treatments to apply to their SSL members.”

The CPD claims the SSL is used in conjunction another program, called Custom Notifications (Special Order S10–05), where police officers, social workers, and community leaders “deliver a joint message … informing [people on the list] of their risk for prosecution based on criminal history, and explaining their opportunities for community help and support.” The CPD itself describes Custom Notifications as “a process that identifies potential criminal actors and victims associated with the continuum of violence. Once identified, the individual is notified of the consequences that will result should violent activity continue.” Between 2013 and 2016, the CPD is reported to have made over 1,400 of these visits.

But beyond these reported numbers, little has been done to publicly evaluate on the effectiveness of the Custom Notifications program. We are not aware of any data detailing how many Custom Notification visits occurred as a result of placement on the SSL. Further, our analysis of the dataset shows that thousands of individuals don’t possess the qualities traditionally associated with a “high risk of criminal activity,” but nonetheless have high scores. 127,524 individuals on the list have never been arrested or shot, but around 88,000 of those are above the cutoff. Presumably, if these individuals don’t share qualities associated with high risk of criminal activity, a good number of these individuals are forecast to be potential victims.

The Custom Notifications program is supposed to present “[o]pportunities for seeking assistance,” but there’s little public evidence of those interventions actually occurring. In fact, the Special Order defining the program speaks in punitive terms, observing that “failure to follow the clear and consistent message to cease participating in gun violence will have specific and cognizable penalties.”

What can we learn from this data?

The Chicago Sun-Times briefly discussed who makes up the highest scoring individuals. One of their findings was that, of the individuals with the maximum possible score of 500, just 22 percent were the repeat offenders that “that police Supt. Eddie Johnson and Mayor Rahm Emanuel have frequently cited as being behind the city’s rise in violence and shooting deaths.” Moreover, as a New York Times analysis found, most shootings did not involve those at the top of the list: “[t]he top 1,400 people have scores of 429 and up, [but] they were involved in less than 20 percent of the city’s total gun violence in 2016.”

Our research into the list also found that more than a third of individuals on the list have never been arrested (133,474) and two-thirds of the list have been arrested at least once for any crime (265,210). This contradicts the CPD claim that the list consists of only those with an arrest record.

Other notable numbers:

126,904 individuals on the list have never been arrested or a victim of a crime, and 88,592 of that group have a score greater than 250.

127,524 individuals on the list have never been arrested or shot, and 89,160 of that group have a score greater than 250.

1,551 individuals have not been arrested or shot, but have been identified as gang-affiliated. 1,318 of that group have a score greater than 250 (note that the CPD has claimed that the most recent version of the SSL does not use gang affiliation as a variable in their algorithm).

823 individuals who have never been arrested but were victims of either a shooting, battery, or assault are on the list, and 763 of that group have a score greater than 250.

What do we still not know?

First, we still don’t know the full range of ways in which an individual arrives on the list. If you’re one of the nearly 400,000 people on the SSL, how did you get there?

So far, according to the Sun-Times’ reporting, we know that the list encompasses “everyone who has been arrested and fingerprinted in Chicago since” 2013. But it’s unclear if those are the only ways to end up on the list. 126,687 listed individuals have never been arrested, never been a victim of gun violence, and never been party to violence. Were they all fingerprinted, for other reasons, or is the story more complex?

Second, when people make positive life choices that reduce their risk — whether thanks to CPD’s custom notifications or otherwise — how will those choices be reflected in their scores? In other words, apart from simply getting older, what can a person do to lower their score or be removed from the list?

Could the data drive toward a different approach to crime?

It’s incredibly rare — and valuable — to see the public release of the underlying data for a predictive policing system.

Ultimately, the release reminds us that what gets measured, gets managed. The information included in the Strategic Subjects List is information provided when an individual is arrested, or census data. And so far (at least according to RAND’s analysis) the list seems to be used primarily to support traditional, punitive policing tactics.

But it’s worth considering a different model. What would it look like to consider other factors that might also correlate to criminal activity? Would taking a more holistic approach help create different interventions that could reduce the crime rate in the city? Are the current interventions already occurring too late? It has been shown that early childhood interventions are not only successful in decreasing delinquency, but are also cost effective. Either way, knowing how interventions are tied to a predictive system is incredibly important.

Without any line of sight into how a predictive system informs policing strategy, we can’t be sure how interventions are being shaped.

Recent funding from the Department of Justice’s Smart Policing Initiative was supposed to support “further development of the Strategic Subject List (SSL) software to improve performance [and] … greater differentiation between offender and victim.” As Yale University sociologist Andrew Papachristos — whose research helped inspire the original version of Strategic Subject List — argued last year, the CPD faces a crucial choice. Should it “[t]reat its list as offenders or as potential victims?” “The real promise of using data analytics to identify those at risk of gunshot victimization lies not with policing, but within a broader public health approach.”

1

In the dataset, an individual’s trend in recent criminal activity is a value given to an individual between -8.2 and 7.3. Every person in the dataset is assigned a “trend in criminal activity” value. This value is created by the CPD, but has never been explained and there is no information for how this number is calculated. We imagine that, a higher score is correlated with more recent arrests. Our analysis only shows a medium correlation between the most recent date of police contact and this value. Nevertheless, this value heavily influences an individual’s overall SSL score. Thus, we’re missing critical information to understand what appears to be a critical variable in the SSL model.

1

While gang affiliation was used in this version of the dataset, the CPD has since claimed that the most recent version of the SSL does not use gang affiliation as a variable in their algorithm: “And gang membership is no longer considered because it wasn’t very good at predicting involvement in shootings as either gunman or victim, though the police say they aren’t sure why.”

1

See, e.g., http://4abpn833c0nr1zvwp7447f2b.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/RAND_Response-1.pdf

1

“The information displayed [on the SSL Chicago data portal] represents a de-identified listing of arrest data from August 1, 2012 to July 31, 2016.” See https://data.cityofchicago.org/Public-Safety/Strategic-Subject-List/4aki-r3np.

Related Work

In a piece published in Slate, Logan argues that popular analysis of predictive policing systems too often focuses on their predictions about the future, and less about the historical data upon which they rely.

PolicingLaw enforcement’s blind faith in a tool that doesn’t always work — a tool that can easily finger the wrong person, with terrible results — provides the central tension for that blockbuster film, and a vital lesson for our present.

PolicingTogether with the Leadership Conference, Upturn releases the latest version of our scorecard that evaluates the police body-worn camera policies in 75 major U.S. cities. It continues to show a nationwide failure to protect the civil rights and privacy of surveilled communities.

Policing