Leveling the Platform

Real Transparency for Paid Messages on Facebook

Aaron Rieke and Miranda Bogen

ReportExecutive Summary

Facebook runs the world’s largest social network. The company makes money by selling the opportunity to reach its users. Facebook delivers targeted, prioritized messages — from those who can pay — to users who might not otherwise see them. These messages vary widely, and extend far beyond ads for consumer goods.

Facebook recently announced new measures to keep advertisers on its platform accountable — including a promise to make all ads on its platform visible to anyone who cares to examine them.

On its face, this would seem to be an important change, in areas reaching far beyond politics. Civil rights groups could audit housing and credit ads for illegal discrimination. Consumer protection authorities could root out bad actors who target the vulnerable. And journalists could track how sponsored messages are shaping the public debate.

Unfortunately, we find that Facebook’s concrete plans fall short of its laudable commitments. This report details steps that Facebook must take to deliver fully on what it has promised.

This report is the first rigorous, independent evaluation of Facebook’s new ad transparency plans. We evaluated the company’s planned ad transparency interface (parts of which are currently being piloted in Canada); tested Facebook’s advertising tools and APIs; conducted a thorough review of the company’s technical documentation and legal terms; and interviewed researchers, advocates, archivists, and journalists.

Findings

Facebook’s ad transparency tools don’t include an effective way for the public to make sense of the millions of ads running on its platform at any given time. If public actors cannot search, sort, and computationally analyze ad data, they have little hope of holding advertisers accountable.

Facebook has not yet committed to disclose critical pieces of the puzzle for most ads, such as how the ad is targeted and the size and nature of the audience it reaches. Without such data, the public cannot diagnose or track the most important, widespread problems, including discriminatory advertising.

Deciding which ads are “political” is a flawed approach. The company’s currently announced goal is to use AI to help identify “political” ads, and to offer some additional information about the ads in that special category. But AI can’t make the distinction cleanly, and neither can humans.

Facebook’s existing legal and technical infrastructure allows for the changes proposed in this report. Facebook already designates ad content as being “available to anyone” in its data policies. And an examination of the company’s Marketing APIs show that it already retains copies of all ads.

Recommendations

Facebook should make ad data publicly accessible through a robust programmatic interface, with search functionality. Ad transparency must allow members of the public to make sense of an individual advertiser’s behavior, and must allow them to locate ads of interest across the platform.

Facebook should provide a strong baseline of access to all ads. Bad actors are constantly seeking new ways to leverage Facebook’s powerful tools, and the search for problems must not be limited to special categories ads.

Facebook should disclose more data about ads’ reach, type, and audience. Ad transparency must include enough data for policy researchers and public advocates to conduct meaningful analyses and spot important trends. This includes information about how the ads were targeted and ultimately delivered.

Introduction

Facebook's business model is vulnerable to abuse. Recently, the company promised to empower the public to "help keep advertisers accountable." This report details steps that Facebook must take to deliver.

Facebook runs the world’s largest social network. Billions have joined, free of charge. The company makes money by selling the opportunity to reach its users. Facebook delivers targeted, prioritized messages — from those who can pay — to users who might not otherwise see them. These messages vary widely, and extend far beyond ads for consumer goods. At their best, they can help a student find a tutor or a single parent connect with a job placement service. At their worst, they can mask illegal discrimination or propel foreign propaganda.

This business model is vulnerable to a range of abuses. Fraudulent opioid rehab centers seek unsuspecting patients, housing providers can illegally discriminate with ease, “affiliate marketers” peddle scams, conversion therapy organizations have targeted LGBT youth, and politically motivated groups have sponsored misleading messages about voting.

Recently, and most prominently, Russian operatives used Facebook ads to try to exploit divisions in American society during the 2016 presidential election. In the wake of this revelation, and amid mounting pressure from lawmakers, regulators, and advocates, Facebook promised improvement. The same day it handed over details about the Russian ads to Congress, the company announced new measures to keep advertisers on its platform accountable.

Facebook promised to make “all ads on the platform visible to anyone who cares to examine them.”

A key part of Facebook’s announcement was a promise to make “all ads on the platform visible to anyone who cares to examine them.” The company has said it wants to establish a “new standard” for ad transparency that will help “everyone, especially political watchdog groups and reporters, keep advertisers accountable for who they say they are and what they say to different groups.” Acknowledging that it is “not always possible to catch” harmful or illegal advertising, Facebook pitched this new transparency as a way to help prevent a repeat of the past, and stop yet-unseen malicious activity.

Taken at face value, this is an exciting promise. Civil rights groups could audit housing and credit ads for illegal discrimination, and shed light on race-based voter repression. Consumer protection authorities could root out bad actors who target the vulnerable. Wildlife preservation advocates could investigate endangered species trafficking. Journalists could track how money fuels disinformation campaigns. And, of course, political ads could be fact-checked and more widely debated.

“We support Congress passing legislation to make all advertising more transparent, but we’re not going to wait for them to act.”

Mark Zuckerberg, January 31, 2018, https://www.facebook.com/zuck/posts/10104501954164561.

Unfortunately, Facebook has yet to realize its commitment. A close review of the company’s ad transparency plans, still under development, reveals several key shortcomings:

Facebook’s plans do not include an effective way for the public to make sense of the millions of ads running on its platform at any given time. Ad transparency without robust programmatic access, including search functionality, will be hamstrung by design, leaving users to sort through an impossible number of messages by hand.

Facebook has not yet committed to disclose critical pieces of the puzzle for most ads, such as how the ad is targeted and the size and nature of the audience it reaches. Without such data, the public cannot diagnose or track the most important, widespread problems, including discriminatory advertising.

Deciding which ads are “political” is a flawed approach. The company’s currently announced goal is to use AI to help identify “political” ads, and to offer some additional information about the ads in that special category. Unfortunately, there’s no good way to decide which ads fall under such a rule, since the question of which messages are “political” is itself political. AI can’t make the distinction cleanly, and neither can humans.

Facebook can do better. The company’s existing technical infrastructure, policies, and contracts pose no barriers to dramatically more useful ad transparency. For example: Facebook already designates ad content as being “available to anyone” in its data policies. It already retains copies of all ads and details about their delivery, even after ads finish running. And it already has powerful technical infrastructure that could provide state-of-the-art, programmatic access to all of the ads on its platform.

Amid growing concerns about user privacy, it is important to emphasize that users’ personal data are entirely distinct from the paid, commercial messages that fuel Facebook’s profits. Recently, Facebook pledged to reduce the ways it allows users’ data to be shared outside of the platform. However, these steps, while important, do relatively little to address how that same data is actually used within the platform — in partnership with advertisers — to propel targeted, paid messages.

Facebook must do better. First, the company should provide useful, robust access to all of the data it has already committed to disclose. Transparency of internet-scale activities must come with internet-scale tools. Second, Facebook should provide a strong baseline of access to all ads, not just those identified as “political” in nature. Drawing and enforcing boundaries around political content will be difficult, and leave wide swaths of content unaddressed. Finally, Facebook should make more ad metadata available for public inspection. At minimum, the company should disclose, at least in broad terms, the size and nature of each ad’s audience. More detail about ads’ targeting and engagement, if disclosed in appropriate and privacy-preserving ways, would further aid the public in diagnosing and addressing a wide range of illegality, discrimination, and abuse.

This report addresses Facebook’s specific tools and commitments, but Facebook is far from the only company with room for improvement.

We urge Facebook to publicly commit to detailed, time-bound plans to address these recommendations; develop a concrete management strategy for achieving them; and define key performance indicators against which the public can judge the company’s progress. Facebook should also discuss these issues with civil society stakeholders and advertisers. Getting ad transparency right would signal Facebook’s sincere interest in restoring trust that is quickly eroding between the company and the public.

Moreover, by taking these steps, Facebook can lead the way for other peer platforms — all of which are wrestling with similar issues — toward a much-needed robust standard of digital advertising accountability beyond the confines of politics. While this report addresses Facebook’s specific tools and commitments, Facebook is far from the only company with room for improvement.

This report proceeds as follows. First, we summarize the mechanics of advertising on Facebook and define some basic terminology. Second, we argue that digital ad transparency efforts must go beyond disclosures designed for individual users; they need to enable meaningful public scrutiny. Finally, we detail our technical and policy recommendations, which we consider a “minimum viable product” for Facebook’s own ad transparency efforts — and a benchmark for the efforts of peer platforms.

The Mechanics of Facebook Advertising

An understanding of how Facebook ads flow through the company’s social network is key to appreciating the need for — and the technical particulars of — effective ad transparency.

There is more to Facebook ads than meets the eye. Facebook ads are designed to blend in naturally alongside non-paid messages on the platform. Whenever possible, Facebook shares social information alongside these paid messages, like if a user’s friend has reacted or commented, in the same way it does for posts from friends. Ads can be shared widely, and live beyond their budgets — often without indication that their distribution was once subsidized. And they can be targeted with remarkable precision.

This section describes basic concepts needed to understand the recommendations that follow. First, we describe how users and pages create and share posts, and some key differences between the two. Next, we define “ad,” and explain how users encounter them on Facebook. Finally, we outline the powerful tools Facebook gives advertisers to target users, based on their personal data.

Posts, Users, and Pages: The Basic Social Building Blocks

The basic unit of communication on Facebook is a post. Posts come in different shapes and sizes and can contain different types of content including text, images, video, and links. Posts are attributed to a single profile. There are several different kinds of profiles on Facebook, but this paper is concerned with user profiles (“users”) and page profiles (“pages”), which are together sufficient to discuss most advertising activity on the platform.

Only pages can pay to push their posts to users who might not otherwise see them.

A user typically represents a single person on Facebook. Pages, by contrast, represent a public entity like a business, brand, celebrity, or cause. Users can set specific limits on who can see their posts (e.g., friends only, or a subset of friends), while page posts are public, visible even to those who don’t follow that page. Pages must be created by a user, who can appoint other users to help manage that page. In practice, a page for a large business is likely to be staffed by many team members (and an external advertising agency), whereas a small nonprofit’s page might be run by a single user. Facebook does not require pages to disclose the identity of their creator or managing users. And, importantly, pages — and only pages — can pay Facebook to push their posts in front of users who might not otherwise see them.

Users  | Pages  |

|---|---|

| Represents a single person | Represents a public entity |

| Public or private, depending on a user’s settings | Mostly public; indexed by search engines |

| Cannot purchase ads or sponsor posts | Can purchase ads and sponsor posts |

| Not allowed to be used primarily for commercial gain | Often used primarily for commercial gain |

| Roughly 2 billion active users | Roughly 60 million active pages |

Practically speaking, users will encounter posts on Facebook in two main ways. First, they can intentionally visit a user or page profile to see its individual feed, which displays posts created by that profile (and, sometimes, by others who have chosen to contribute to that individual feed). But more often, users are likely reading a personalized news feed that displays a specially tuned mix of posts from their friends, pages they have followed, and pages that have paid to reach them.

| Individual Feed (User) | News Feed | Individual Feed (Page) |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

Ads: Special Posts, Designed to Blend In

Facebook does not formally define “ad” in its public policies, terms of service, or technical documentation. For the purposes of this paper, ad refers to a post that Facebook has, at any time, approved for paid distribution. Paid distribution is when Facebook shows a user an ad in exchange for payment or the potential of payment. More simply, an “ad” is a post that has, at any time, been backed by money. As we explain below, ads are built to seamlessly coexist with, and can at times be nearly indistinguishable from, other posts on Facebook.

An “ad” is a post that has, at any time, been backed by money.

Facebook offers many different ways to design ads. Ads can be designed to look like unpaid posts, and unpaid posts can be turned into ads with a few clicks. Moreover, advertisers can choose among a range of different post formats that are designed to help them achieve different goals.

For example, a business that wants to encourage shopping might choose a carousel of product images. A charity soliciting donations might be sure to include a prominent “Donate Now” button. An organization hoping to raise awareness about its issues might mention a news article written by a third party, selecting the format that looks similar to other users’ posts in hopes people will share it.

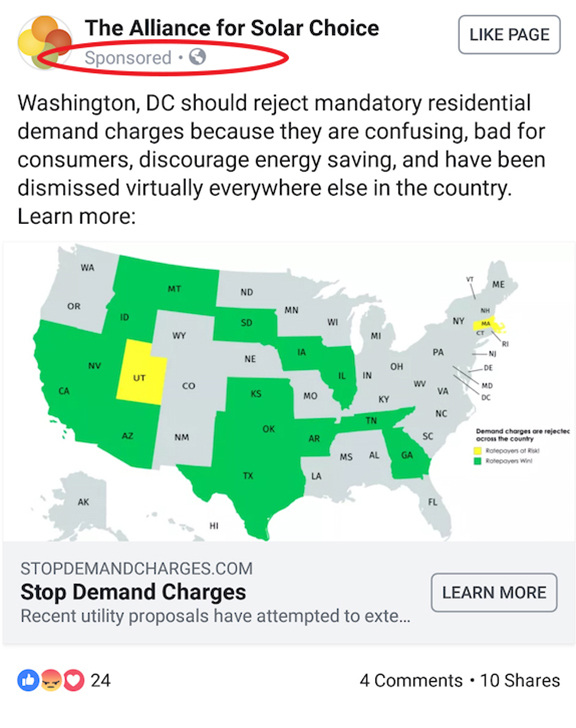

Users can see ads through paid or organic distribution. When a user sees an ad via paid distribution, it is subtly marked as “Sponsored,” and the user can examine some of the reasons they are seeing it. Organic distribution, by contrast, refers to any other non-paid way a user might see the ad. For example, a user’s friend — who saw the ad via paid distribution — might have shared the ad, or a user might have visited the page’s own feed on which the ad was visible. In these cases, the ad is not marked with the “Sponsored” label, and depending on the ad’s design might be nearly indistinguishable from another type of post.

| Paid Distribution | Organic Distribution |

|---|---|

|  |

| Labeled “Sponsored” | No “Sponsored” label |

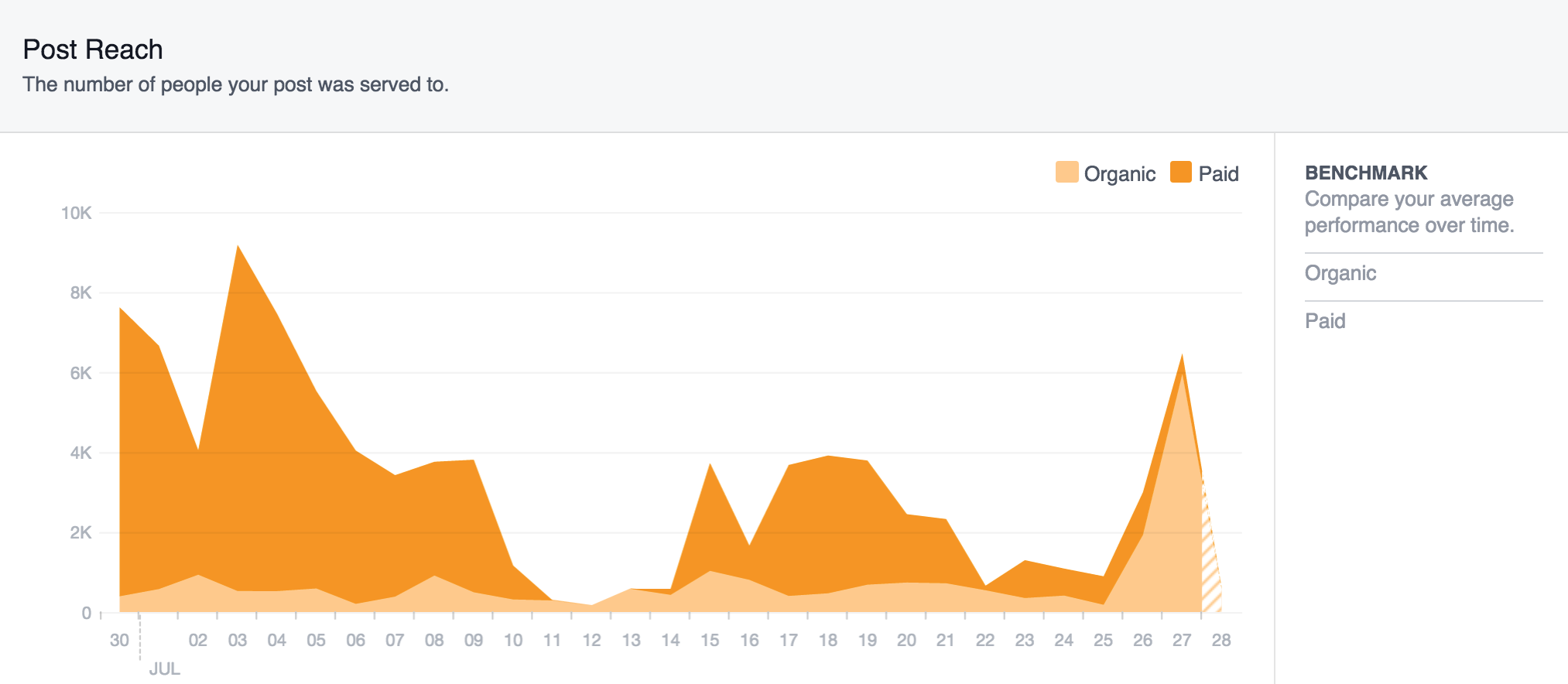

An ad can continue to circulate via organic distribution long after its budget for paid distribution expires. For many advertisers, this is an important feature: It allows them to sponsor a post that they hope will “go viral,” and continue to reach users beyond its “ad run.”

Facebook Post Reach

Facebook analytics showing how a post can shift between paid and organic distribution over time (Source)

For example, a page might pay enough to show a post to 1,000 users through paid distribution. If those users share the ad widely, it might end up being shown for free to millions more users — who would have no way of knowing that money had been spent on the post.

In sum, the boundary between ads and other types of posts can be porous. Ads are designed to exist seamlessly among other kinds of posts that users see in their news feeds. These posts can move in and out of paid distribution. Paid posts can long outlive the money initially allocated to display them. And in many cases, it can be infeasible for users to determine when a post was initially propelled by money before going viral.

Targeting: Dispatching Ads with Surgical Precision

Typically, advertisers only want certain kinds of users to see their ads. Facebook allows advertisers to target ads with power and precision, choosing what kinds of users get to see, or are excluded from seeing, their messages.

The most basic targeting tools provided by Facebook fall into a category the company calls core audiences. These include rudimentary demographic factors like location, age, gender, language, and field of study, based on information people provide to Facebook when filling in their profiles, as well as pages a user has liked. They also include hundreds of additional inferred categories based on details like what sorts of pages and content users interact with on and off Facebook. For example, advertisers can target based on users’ inferred political leanings (“Likely to engage with political content (conservative)”), multicultural affinity (“Hispanic (US - Bilingual)”), and household composition (“Family-based households”).

Core Audiences

| Information Type | Examples |

|---|---|

| User-provided | Age, gender, location, language, university, field of study, employer, liked pages |

| Inferred from Facebook Activity | Interests (e.g. “Movies,” “Current events,” “U.S politics (liberal),” “LGBT community”) Behavior (e.g. “Recent mortgage borrower,” “Returned from travels 1 week ago,” “Close friend of expat,” “Spending methods: Primarily cash” |

Advertisers can also specify their own custom audiences — lists of specific people provided by the advertiser. For example, a custom audience might consist of a retail store’s customers, likely voters from a political database, visitors to the page owner’s website, or others the advertiser has a special interest in reaching. Facebook anonymously matches information on these lists — commonly e-mail addresses and phone numbers — to users of Facebook, and serves those users ads.

Custom Audiences

| Information Type | Examples |

|---|---|

| Offline data | Retail store customers, likely voters from voter file, new email subscribers, past donors and volunteers |

| Real-time data | All website visitors in the past 30 days People who interacted with an advertiser’s Facebook post or ad People who responded “Interested” to an advertiser’s Facebook events |

Finally, one of the most powerful targeting tools at advertisers’ disposal is lookalike audiences. Lookalike audiences allow an advertiser to target people who share similarities with a predefined custom audience. Once the advertiser selects one of its custom audiences as a source, Facebook uses machine learning to find and target people whose characteristics and behavior resemble those of people on the original list. In effect, lookalike audiences allow advertisers to say “show my messages to people who are like these people I already know.”

Lookalike Audiences

| Information Type | Who is Included |

|---|---|

| Derived from a Custom Audience | Based on a source audience (e.g. Custom Audience, app users, page fans) Source audience must contain at least 100 people from a single country Includes between 1-10% of the total population of countries targeted |

Facebook does not say what factors its algorithm considers when determining whether someone is similar to the source audience for a lookalike audience. In fact, Facebook does not even know what characteristics of the source audience an advertiser wants to replicate. In turn, the advertiser is not given the identities of the lookalike users that Facebook finds. However, independent experiments have shown that distinct racial affinity or political affiliation of a source audience can be replicated in the resulting lookalike audience.

Facebook has touted the efficacy of lookalike audiences in shifting political opinions and driving direct response.

Facebook has touted the efficacy of both custom and lookalike audience tools in shifting political opinions and driving direct response. In fact, an internal white paper found that the Trump presidential campaign spent more than a quarter of its Facebook budget on custom and lookalike lists, a significantly higher amount than the Clinton campaign. We expect that advertisers will likely turn even more to custom and lookalike audience tools to efficiently reach receptive audiences.

Ad Transparency Must Enable Meaningful Public Scrutiny

Facebook’s business model faces systemic challenges. Effective ad transparency must also be systemic, enabling collective accountability efforts.

Any transparency effort must be judged in light of its goals. Like many companies, Facebook uses the word “transparency” to describe different disclosures for different audiences. Sometimes, transparency is for individual users. For example, at the encouragement of European regulators, Facebook has made its data policies more “transparent” — that is, easier to read. Other times, transparency is for advertisers. For example, after miscalculating how much time users spent watching videos on its platform, Facebook promised to “increase transparency” of its metrics by partnering with third parties to help verify its analytics. In other cases, transparency is for the public at large. For example, in response to concerns about government surveillance, Facebook maintains a “Transparency Report” tracking government requests for user data.

“Part of the point of transparency is both to inform the public debate and to build trust.”

Facebook’s ad transparency effort must be designed for the public, in the broadest possible sense. It must go beyond labeling ads and providing notices to individual users, necessary as these features are. The company seems to agree: It has said its ad transparency plans are designed in part for those who act on its users’ behalf, including reporters and political watchdog groups. It purportedly wants this transparency to help it catch “malicious actors faster” and to prevent “more improper ads from running."

Ad transparency should allow the public to both investigate known issues — ranging from consumer predation to illegal discrimination to misinformation — and to identify new ones. Facebook should welcome the help on both fronts. The company cannot provide the safest possible community for its users on its own. It already relies heavily on input from domain experts to inform and enforce its advertising policies. It will always struggle to address issues that are subjective and politically charged. And it does not yet have robust cultural and linguistic competence to identify novel cases of subtle discrimination across the globe.

Example: Uncovering Census Repression

A full and accurate counting of everyone in the United States is necessary for the proper functioning of government, civil society, and the private sector. Underrepresented communities have an especially strong stake in the accuracy, completeness, and availability of Census Bureau data.

Unfortunately, some have threatened to try to repress census turnout by pushing misleading or threatening messages on social media.66 Some worry that such plans, if executed, could lead to “a population undercount that would disproportionately harm states and cities with large immigrant communities.”67

A robust ad transparency interface would allow a civil rights organization to quickly identify paid posts that use terms like “census,” to diagnose such threats. If problematic posts were discovered, they could be reported to Facebook (if they violated Community Standards), covered in the media, or discussed with members of affected communities.

Ad transparency should also allow the public to measure and verify Facebook’s own efforts to police its platform. The company has recently pledged to take a broader view of its responsibility, and to invest more heavily in automated review of ads and organic content. However, there is plenty of evidence that technology will provide only partial solutions. The company cannot yet fully enforce the rules it has already adopted, and has struggled to effectively identify important kinds of ads for special treatment. As these efforts evolve, public oversight can help identify problems, suggest fixes, and hold Facebook accountable for its commitments.

In short, Facebook faces systemic problems that go to the heart of how it makes money. Only a systemic transparency response will be sufficient.

Recommendations

Internet-scale ad transparency requires internet-scale tools and data. Facebook is already well equipped to offer both. Here’s what the company should do next.

To empower the public to hold both advertisers and the platform accountable, Facebook must augment its existing ad transparency steps. Below, we offer three recommendations, and explain why each is necessary. First, we recommend that ad data be provisioned in a useful way. Second, we recommend that a strong baseline of transparency be provided for all ads, not just for “political” ads. Finally, we recommend that more ad data be disclosed.

Provide Ad Data in a Programmatic and Searchable Form

Recommendation: Make ad data publicly accessible through a robust, programmatic interface with search functionality. Access to the interface can be governed by reasonable contractual and technical measures (e.g., non-commerciality requirements and rate limitations), but should be made available for wide public use. This recommendation does not extend to any disclosures of user data, or data that might identify a user.

Ad transparency must, at minimum, allow members of the public to make sense of an individual advertiser’s behavior, and to locate ads of interest across the platform. Each day, there are millions of ads circulating on Facebook, sponsored by millions of different advertisers.72 It is extraordinarily difficult to make sense of such large-scale activity, even for Facebook itself. If outsiders cannot search, sort, and computationally analyze this data, they have little hope of holding advertisers accountable. This is especially true given that many issues of concern may play out on a national — or even international — scale.

If public actors cannot search, sort, and computationally analyze ad data, they have little hope of holding advertisers accountable.

Today, Facebook’s transparency effort falls far short. The ad transparency interface that Facebook is piloting in Canada requires users to manually load a single page’s ads in a paginated view — and only displays ads that are currently running.73 This design decision dramatically constrains accountability research efforts. For example, someone interested in investigating “opioid counseling” ads would first have to manually determine which pages might be sponsoring related posts (e.g., by cross-referencing business names identified in other research or interviewing individual Facebook users) and then review those pages — slowly — by hand. In principle, every relevant ad might be “visible,” but this is little consolation if they cannot be examined at any reasonable scale. As discussed below, Facebook is offering somewhat more powerful access to ads identified as being “political” in nature — but this approach has its own limitations.

Loading ads by hand in the current page transparency view.

This limited user interface might tempt a public investigator to resort to browser plug-ins or custom software to analyze ad data at scale. But this would be risky: Facebook prohibits any kind of “automated data collection,” even of public data.74 Technological self-help, even to access data Facebook and page owners have purposefully made public, could result in loss of access to the platform.

Facebook should provide a better way for the public to review ads. Fortunately, the company already has the infrastructure to provide the public with more useful access. Many platforms offer two kinds of ways to access their data: user-facing interfaces, like websites and apps, and Application Programming Interfaces (APIs), designed for use by computer programs. Facebook is no different. For years, it has provided data in powerful and flexible ways to developers (through its Graph API) and marketers (through its Marketing API). This is exactly the kind of technical infrastructure needed for public accountability work today.

Example: Preventing Student Debt Scams

Student debt relief scams are pervasive on the internet.75 In particular, fraudsters often target alumni of for-profit colleges, who disproportionately file loan claims alleging they’ve been misled or defrauded by federally approved colleges and universities.76

Usually, these student loan relief scammers use online ads to reach struggling borrowers.77 However, advocates struggle to understand the size, scope, and particulars of these practices on Facebook.

A robust ad transparency interface would allow a regulator or nonprofit researcher to study ads using terms like “student loan” and “debt forgiveness” to learn about the size and scope of these predatory practices. Where applicable, they could also report offending ads to Facebook for violating its policies.78

Facebook has recently come under fire for sharing via APIs sensitive user data that was subsequently misused, and has taken significant steps to limit API access to users’ personal information.79 It is important to emphasize: This paper makes no recommendation concerning how Facebook provisions access to user data. Rather, it advocates that page data — data that is of a much more public, often commercial nature — be made available in a robust, flexible way for public accountability purposes.80

Go Beyond “Political” Ads

Recommendation: Provide a strong baseline of access to _all_ ads, not just those identified as "political" in nature.

Facebook has committed to special treatment of “political” ads, a designation which includes both electoral and issue ads.81 Facebook will make ads identified as belonging in this category available in some kind of searchable database (but has not committed to making these ads programmatically available).82 The company will also append labels and disclaimers to these ads and require related advertisers to undergo special authentication steps.83 These are welcome reforms that are responsive to pressure from lawmakers and regulators.84

Political ads may well deserve special attention, but drawing and enforcing lines around this category will be difficult. At the outset, defining what counts as “political” will be a fraught process. Facebook is currently “working with third parties to develop a list of key issues, which [they] will refine over time.”85 But even assuming best efforts, the company will never be able to exhaustively define categories of ads that fully capture “political topics that are being debated across the country” — let alone around the world.86

What should count as an issue ad?

Moreover, Facebook plans to use artificial intelligence to detect political ads,87 but the company has struggled to follow through on similar, albeit much simpler, commitments in the past.88 Automated tools are a long way from being able to parse nuanced language, especially where contextual elements are critical.89 Inevitably, many important political ads will slip through the cracks.90

Given these difficulties, Facebook should welcome public scrutiny of all ads, regardless of whether they have been labeled as political. With broader access, public actors will be better positioned to help refine the scope of “political” ads over time, and spot errors in Facebook’s automated tools.

Automated tools are a long way off from being able to parse nuanced language, especially where contextual elements are critical.

Even if defining and detecting all political ads was possible, such an approach would still capture only a subset of important paid messages. Abuses of Facebook’s ad system reach far beyond the realms of politics, ranging from promotions for potentially fraudulent opioid rehab centers,91 to aggressive for-profit college “lead generation,”92 to anti-vaccination misinformation.93 Making all ads just as accessible and searchable as political ads would give public interest researchers a critical window to spot and track potentially harmful messages, as well as provide an important baseline for continued debate about how and when to label political ads.

In short, robust ad transparency should cover the full gamut of sponsored activity on Facebook. It is important that Facebook provide a baseline of strong transparency — as described in the other recommendations — for all ads, not just those deemed political.

Disclose More Ad Metadata

Recommendation: Disclose data about ads' reach, type, and audience — especially for ads that implicate important rights and public policies.

Ad transparency must include enough data for policy researchers and public advocates to conduct meaningful analyses and spot important trends. Sometimes, the content of ads alone can be helpful. But more data is usually needed to detect impact and intent. Without it, researchers will all too often be left in the dark.

Unfortunately, for most ads, Facebook has thus far chosen to disclose only the ad’s content. With the exception of political ads, Facebook currently hides important metadata such as the number of user interactions (e.g., “Likes”), shares, and video views from its ad transparency interfaces. It also does not disclose category labels for ads that the company has identified as offering housing, employment, or credit — the types of ads many would be most concerned about. And it does not reveal any information about how or to whom the ad was targeted. Each of these omissions has consequences.

| Type of data | What is it? | Why is it important? |

|---|---|---|

Ad Creative Ad Creative | The content of an ad (any page post touched by money), including headlines, images, text, links, and calls to action. | Needed to diagnose malicious, illegal or otherwise problematic ads. |

Category Category | An internal label that Facebook applies to certain types of ads (e.g. federal election; housing, credit, or employment). These labels facilitate the enforcement of special rules that apply to these ad categories. | Needed to enable researchers to focus their efforts on important categories of ads, and to diagnose problems with Facebook’s classification processes. |

| How many unique users saw the post at least once. | Needed for researchers to focus their efforts on widely-viewed ads, and to prevent high-volume advertisers from obscuring their activity. | |

Reactions and Shares Reactions and Shares | How many times users react (e.g. “Like”) or share a post. | Needed for researchers to gauge the audience scale, and audience response, for an ad. |

Ad Spend Ad Spend | How much money an advertiser spent on each ad or ad campaign. | Needed for researchers to focus their efforts on widely-viewed ads, and prevents high-volume advertisers from obscuring their activity. May be legally required for some types of ads. |

Audience Audience | Targeting options specified by the advertiser, including core targeting segments and whether the advertiser used a custom list or lookalike audience. | Needed to detect illegal discrimination and other harms targeted at particular groups. Provides an indication of an advertisers intended audience. |

Demographics Demographics | Demographic details (e.g., age, gender, location) of users who actually saw an ad, regardless of target audience. | Needed to detect illegal discrimination and other harms targeted at particular groups. Actual audience data may be the only way to feasibly evaluate custom and lookalike audiences. |

First, Facebook has not yet provided a way for researchers to gauge most ads’ reach. This makes it impossible for an outsider to make sense of a high-volume advertiser’s activity. Some advertisers run many thousands of ads at the same time; Facebook offers tools for them to do so with ease.94 Advertisers often run many versions of an ad to test which message is most effective.95 They can then choose to invest the bulk of their budget in the highest-performing versions — or seed the best-performing ads with a small budget and let them propagate organically to a wider audience. Donald Trump’s presidential campaign, for example, boasted it ran 50,000 different ads per day.96 Without access to data indicating which ads are actually distributed and seen at scale, there is no way to hone in on the ads with the largest runs.

Second, Facebook does not make it possible to identify the ads it has already flagged as deserving extra scrutiny.97 In late 2016, responding to concerns by policymakers and civil rights leaders, Facebook began automatically identifying ads offering housing, employment, or credit.98 These labels allow the company to prompt advertisers to agree to Facebook’s antidiscrimination policies, and to restrict the use of certain ad targeting segments. However, the labels could also help outside researchers focus their attention on these important kinds of ads (without having to create their own classifiers). Moreover, by making these labels and others like them public, outside groups could help Facebook spot labelling mistakes — an issue with which the company has already struggled.99

“Sometimes a combination of an ad’s message and its targeting can be pernicious.”

Third, for most ads, Facebook has not yet promised any public disclosures about how ads are targeted. Targeting data is important because, as the company has recognized, sometimes a “combination of an ad’s message and its targeting can be pernicious.”101 In fact, some of the most important ad problems can only be spotted when ad targeting can be evaluated alongside content. Targeting data is essential to assess discrimination of all kinds.102 It is also crucial to spot ad campaigns that might seek to offend, misinform, or endanger particular communities based on race, religion, or sexual orientation.103 And it can help outside observers spot and keep track of important issue advocacy campaigns.104

Example: Age Discrimination in Employment Ads

In December 2017, ProPublica and The New York Times revealed that a number of large corporations used Facebook’s ad platform to place recruitment ads that were tailored for, and targeted toward, particular age groups.105 Facebook’s Vice President of Ads argued that these marketing strategies are permissible when “broadly based and inclusive, not simply focused on a particular age group.”106

A watchdog group could further investigate the legality of these ad campaigns, but only with access to both their content and some sense of their targeting strategies. An ad transparency system would allow for both, helping to ensure that Facebook is not implicitly allowing age-biased recruiting and hiring practices.107

We see two complementary approaches to making ad targeting more transparent. First, Facebook could disclose information about the targeted audience, as specified by the advertiser. This would include, for example, a list of core targeting segments or a simple indication that a custom list or lookalike audience was used.108 The company already makes a small subset of this data available to individual users.109 It would be of even greater value if opened to public scrutiny.

An outcome-based approach may be the only way for the public to evaluate custom and lookalike audiences.

However, this approach has a critical limitation: Facebook cannot disclose the contents of a custom list or all of the correlations that led to the creation of a lookalike audience without offending both user privacy and advertiser confidentiality.110 Accordingly, Facebook could also disclose certain information about the demographics of the users who actually saw the ad. This kind of outcome-based approach may be the only way to evaluate custom and lookalike audiences.111 The company has already taken a step down this road: For political ads, it will soon “[p]rovide demographics information (e.g. age, location, gender) about the audience that the ads reached.”112 This is an approach Facebook should continue to refine, and deploy more broadly.113

We urge Facebook to engage with civil society stakeholders, advertisers, and privacy experts to further discuss how, when, and under what circumstances to disclose additional targeting information. Among all the kinds of ad data, targeting data is likely to be the most contentious. Advocates should describe the kinds of disclosures they need to hold advertisers accountable. Advertisers should identify legitimate concerns about competition and business confidentiality issues. And privacy experts should be on the lookout for circumstances when disclosures of information might implicate users’ privacy, especially when target audiences are small.

There will be room for compromise. It may be appropriate to disclose targeting for the most important types of ads, or to impose enhanced contractual requirements for those accessing more detailed targeting information through a transparency interface. In any case, Facebook has plenty of tools — both technical and legal — with which to properly balance business interests and important public accountability goals.

Conclusion

Facebook has made an important commitment to ad transparency. Public actors have been, and will continue to be, vital to diagnosing, and thinking critically about how to address, a wide range of abuses on internet platforms. Journalists, public interest groups, and researchers stand ready to help make sense of how money helps propel misinformation, predation, and discrimination across the platform — and to hold both platforms and their customers accountable. By taking the additional steps outlined in this report, Facebook would give the public powerful tools to further such critical work, and demonstrate its commitment to taking a broader view of its responsibility.

“We recognize this is a place to start and will work with outside experts to make it better.”

We urge Facebook to discuss these issues with civil society stakeholders and advertisers, and publicly commit to detailed, time-bound plans to address these recommendations. Getting ad transparency right would signal Facebook’s sincere interest in restoring trust between the company and the public, and establish a much-needed new standard for the broader industry.

Appendix: Detailed Recommendations

Overall Recommendations

Recommendation 1: Make ad data publicly accessible through a robust programmatic interface with search functionality. Access to the interface can be governed by reasonable contractual and technical measures (e.g., non-commerciality requirements and rate limitations), but should be made available for wide public use. This recommendation does not extend to any disclosures of user data, or data that might identify a user.

Recommendation 2: Provide a strong baseline of access to all ads, not just those identified as "political" in nature.

Recommendation 3: Disclose data about ads' reach, type, and audience — especially for ads that implicate important rights and public policies.

Detailed Recommendations for Ad Data Disclosures

| Type of data | What is it? | Why is it important? | Facebook’s Contemplated Disclosure | Recommended Disclosure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Ad Creative Ad Creative | The content of an ad (any page post touched by money), including headlines, images, text, links, and calls to action. | Needed to diagnose malicious, illegal or otherwise problematic ads. | Content for currently running ads. Political ads will be made available for a number of years after they run. | Content for all ads, for a reasonable period of time after an ad runs. |

Category Category | An internal label that Facebook applies to certain types of ads (e.g. federal election; housing, credit, or employment). These labels facilitate the enforcement of special rules that apply to these ad categories. | Needed to focus efforts on important categories of ads, and to diagnose problems with Facebook’s classification processes. | No category data. Ads categorized as political will be presented in the user interface. | Category data for housing, credit, employment and political ads, along with any other categories of public interest. |

| How many unique users saw the post at least once. | Needed for researchers to focus their efforts on widely-viewed ads, and to prevent high-volume advertisers from obscuring their activity. | No reach data for most ads. For political ads, Facebook will show the total number of impressions for each ad. | An approximation of reach data for each ad. | |

Reactions and Shares Reactions and Shares | How many times users react (e.g. “Like”) or share a post. | Needed for researchers to gauge the audience scale, and audience response, for an ad. | No reaction or share data. | The number of reactions and shares associated with each ad. Individual user data should be omitted. |

Ad Spend Ad Spend | How much money an advertiser spent on each ad or ad campaign. | Needed to focus efforts on widely viewed ads, and to prevent high-volume advertisers from obscuring their activity. | For political ads, Facebook will show an approximation of how much was spent. | An approximation of ad spend for all ads. |

Audience Audience | Targeting options specified by the advertiser, including core targeting segments and whether the advertiser used a custom list or lookalike audience. | Needed to detect illegal discrimination and other harms targeted at particular groups. Provides an indication of an advertisers intended audience. | No targeting data for any ad. | Additional targeting data for all ads, especially those that implicate important rights and public policies. |

Demographics Demographics | Demographic details (e.g., age, gender, location) of users who actually saw an ad, regardless of target audience. | Needed to detect illegal discrimination and other harms targeted at particular groups. Actual audience data may be the only way to feasibly evaluate custom and lookalike audiences. | No demographic data for most ads. For political ads, basic demographics of users who saw the ad (age, location, gender). | Demographic data for all ads, especially when needed to assess how an ad implicates important rights and public policies. |

About This Report

In preparing this report, we evaluated the Facebook’s planned ad transparency interface (parts of which are currently being piloted in Canada); tested the company’s advertising tools and APIs; conducted a thorough review of the Facebook’s technical documentation and legal terms; and interviewed researchers, advocates, archivists, and journalists.

About the Authors:

Aaron Rieke is a Managing Director at Upturn. He holds a JD from Berkeley Law, with a Certificate of Law and Technology, and a BA in Philosophy from Pacific Lutheran University.

Miranda Bogen is a Policy Analyst at Upturn. She holds a Master’s degree in Law and Diplomacy with a focus on international technology policy from The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts, and bachelor’s degrees in Political Science and Middle Eastern & North African Studies from UCLA.

Upturn combines technology and policy expertise to address longstanding social inequities, especially those rooted in race and poverty.

1

Facebook, Company Info, https://newsroom.fb.com/company-info/ (“2.20 billion monthly active users as of March 31, 2018”) (last accessed May 1, 2018).

1

In some cases, Facebook subsidizes users’ Internet access. See, e.g., Announcing the launch of Free Basics in Nigeria, Internet.org by Facebook, May 10, 2016, https://info.internet.org/en/blog/2016/05/10/announcing-the-launch-of-free-basics-in-nigeria/ (“To date, we estimate that our connectivity efforts, which include Free Basics, have brought more than 25 million people online who wouldn’t be otherwise.”).

1

See, e.g., Written Statement of Eric Gold, Assistant Attorney General of Massachussets, Before the United States House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations “Examining Concerns of Patient Brokering and Addiction Treatment Fraud,” December 12, 2017, https://democrats-energycommerce.house.gov/sites/democrats.energycommerce.house.gov/files/documents/Testimony-Gold-OI-Hrg-on-Examining-Concerns-of-Patient-Brokering-and-Addiction-Treatment-Fraud-2017-12-12.pdf (testifying that patient brokers “solicit a wider audience on-line or through social media, including on Facebook”); Brad Witbeck, How to Use Facebook Ads to Grow Your Addiction Recovery Center, Disruptive Advertising, April 10, 2017, https://www.disruptiveadvertising.com/social-media/addiction-recovery-facebook-ads/.

1

Facebook Sued By Civil Rights Groups For Discrimination in Online Housing Advertisements, March 27, 2018, http://nationalfairhousing.org/2018/03/27/facebook-sued-by-civil-rights-groups-for-discrimination-in-online-housing-advertisements/; Letter from Senator Cortez Masto et al to Mark Zuckerberg, April 17, 2018, available at https://www.cortezmasto.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Cortez%20Masto%20Letter%20to%20Facebook%20Re%20Ad%20Discrimination%20FINAL.PDF (stating that “[w]hile targeted ads can be a tremendous tool for businesses and organizations, the unregulated use of such targeting for housing and emplotmwnt xan faciliate unlawful discrimination.”)

1

Zeke Faux, How Facebook Helps Shady Advertisers Pollute the Internet, Bloomberg Businessweek, March 27, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2018-03-27/ad-scammers-need-suckers-and-facebook-helps-find-them.

1

Fariha Karim, Facebook under fire for targeted ‘gay cure’ adverts, The Times, February 25, 2017, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/facebook-under-fire-for-targeted-gay-cure-adverts-2b7lh0td2.

1

See, e.g., Judd Legum, GOP To Iowans: Your Neighbors Will Know If You Don’t Vote Republican, ThinkProgress, October 31, 2014, https://thinkprogress.org/gop-to-iowans-your-neighbors-will-know-if-you-dont-vote-republican-338b327f4273; Deceptive Election Practices and Voter Intimidation: The Need for Voter Protection, Common Cause, the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, and the Century Foundation, 2012, http://www.commoncause.org/research-reports/National_070612_Deceptive_Practices_and_Voter_Intimidation.pdf (Deceptive practices and voter intimidation, including deceptive emails, robocalls, and Facebook messages, continue to hurt historically disenfranchised voters, and tactics “have become more sophisticated, nuanced, and begun to utilize modern technology to target certain voters more effectively.”).

1

See generally United States of America v. Internet Research Agency LLC, filed February 16, 2018, https://www.justice.gov/file/1035477/download; Alex Stamos, An Update On Information Operations On Facebook, September 6, 2017, https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2017/09/information-operations-update/.

1

Joel Kaplan, Improving Enforcement and Transparency of Ads on Facebook, October 2, 2017, https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2017/10/improving-enforcement-and-transparency/.

1

In September 2017, Facebook announced it would make all active ads visible on advertisers’ pages and “work with others to create a new standard for transparency in online political ads.” Colin Stretch, Facebook to Provide Congress With Ads Linked to Internet Research Agency, September 21, 2017, https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2017/09/providing-congress-with-ads-linked-to-internet-research-agency. Roughly a week later, the company described plans to strengthen enforcement against improper ads, update and expand ad content policies, and “require more thorough documentation from advertisers who want to run US federal election-related ads.” Joel Kaplan, Improving Enforcement and Transparency of Ads on Facebook, October 2, 2017, https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2017/10/improving-enforcement-and-transparency/. Later that month, the company announced it would test its page-based ad transparency feature in Canada, mark election ads with a “paid for by” disclosure, and build a searchable archive for federal-election related ads with additional details on the reach, ad spend, and audience demographics for such ads. Rob Goldman, Update on Our Advertising Transparency and Authenticity Efforts, October 17, 2017, https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2017/10/update-on-our-advertising-transparency-and-authenticity-efforts. In April 2018, the company announced it would broaden its definition of political ad content to include “issue ads,” and mark, disclose and archive them in the same way they planned to for federal election ads. While the company did not define what issues would be included, the announcement indicated that Facebook would “[work] with third parties to develop a list of key issues, which we will refine over time.” Rob Goldman, Making Ads and Pages More Transparent, Facebook Newsroom, April 6, 2018, https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2018/04/transparent-ads-and-pages/.

1

Rob Goldman, Twitter, Feburary 17, 2018, https://twitter.com/robjective/status/964884872882982912 (last accessed March 7, 2018).

1

Joel Kaplan, Improving Enforcement and Transparency of Ads on Facebook, October 2, 2017, https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2017/10/improving-enforcement-and-transparency/; Rob Goldman, Update on Our Advertising Transparency and Authenticity Efforts, Facebook Newsroom, October 27, 2017, https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2017/10/update-on-our-advertising-transparency-and-authenticity-efforts/ (last accessed March 7, 2018).

1

Rob Goldman, Update on Our Advertising Transparency and Authenticity Efforts, Facebook Newsroom, Ocotber 27, 2017, https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2017/10/update-on-our-advertising-transparency-and-authenticity-efforts/ (last accessed March 7, 2018).

1

Senator Cory Booker, Democrat of New Jersey, questioned Mr. Zuckerberg over discriminatory uses of Facebook’s advertising platform to target ads to users by race, and tools that law enforcement officials have reportedly used to surveil activists of color. Transcript of Mark Zuckerberg’s Senate hearing, The Washington Post, April 10, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-switch/wp/2018/04/10/transcript-of-mark-zuckerbergs-senate-hearing/?utm_term=.80b5269d39e6.

1

Ashlee Kieler, CFPB Asks Google, Bing & Yahoo To Help Stop Student Loan Debt Scams That Imply Affiliation With Feds, Consumerist, June 22, 2015, https://consumerist.com/2015/06/22/cfpb-asks-google-bing-yahoo-to-help-stop-student-loan-debt-scammers-that-imply-affiliation-with-feds/.

1

Natasha Bach, Facebook Is Running Ads on Pages Run by Wildlife Traffickers Illegally Selling Animal Parts, Fortune, April 10, 2018, http://fortune.com/2018/04/10/facebook-sec-wildlife-complaint/.

1

Jonathan Zittrain, Mark Zuckerberg Can Still Fix This Mess, The New York Times, April 17, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/07/opinion/sunday/zuckerberg-facebook-privacy-congress.html (explaining that “[m]ost of us won’t spend a Sunday looking through Facebook ads, but public interest groups and consumer protection officials will, and they’ll publicize and be in a position to act on the troubling things they find.”).

1

Journalists are already trying to track Facebook ads by building their own tools, but are constrained by the number of people who opt to install these tools in their internet browsers. See e.g. Julia Angwin and Jeff Larson, Help Us Monitor Political Ads Online, September 7, 2017, https://www.propublica.org/article/help-us-monitor-political-ads-online. Such tools are already bearing fruit: see e.g. Laura Silver, A British Religious Group Is Paying For Targeted Facebook Ads At Irish Voters Ahead Of The Abortion Referendum, Buzzfeed News, April 13, 2018, https://www.buzzfeed.com/laurasilver/a-british-religious-group-is-paying-for-targeted-facebook.

1

Mark Zuckerberg, January 31, 2018, https://www.facebook.com/zuck/posts/10104501954164561.

1

Facebook has committed to expanded disclosures for “federal-election related” ads and “electoral and issue ads.” Rob Goldman, Update on Our Advertising Transparency and Authenticity Efforts, Facebook Newsroom, October 27, 2017, https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2017/10/update-on-our-advertising-transparency-and-authenticity-efforts/ (last accessed March 7, 2018); Rob Goldman and Alex Himel, Making Ads and Pages More Transparent, Facebook Newsroom, April 6, 2018, https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2018/04/transparent-ads-and-pages. However, as we detail below, these ads are only a subset of socially important messages that are purchased on the Facebook platform. Moreover, as Facebook’s disclosure system for these ads is still forthcoming, we have not had an opportunity to evaluate it.

1

Facebook is piloting parts of its new ad transparency toolkit in Canada with plans to launch in the U.S. in the summer of 2018.

1

See, e.g., Facebook Advertising Policies, “Things You Should Know,” Section 13.4, available at https://www.facebook.com/policies/ads/; Facebook Data Policy, Section III, available at https://www.facebook.com/full_data_use_policy. (Facebook’s own ad policies stipulate that “[a]ds are public information, as described in the Facebook Data Policy.” Public information, according to the Data Policy, is “available to anyone on or off our Services and can be seen or accessed through online search engines, APIs, and offline media, such as on TV.”).

1

Facebook for Developers, Ad News, DELETED vs ARCHIVED, October 1, 2014, https://developers.facebook.com/ads/blog/post/2014/09/24/deleted-vs-archived/.

1

Ime Archibong, API and Other Platform Product Changes, Facebook for Developer News, April 4, 2018, https://developers.facebook.com/blog/post/2018/04/04/facebook-api-platform-product-changes/.

1

Twitter promised to launch an ad transparency center where it would show all currently running ads, but the company has been criticized for failing to follow through on its commitment. Alex Kantrowitz, In October, Twitter Promised An Ad Transparency Center In ‘Coming Weeks.’ Where Is It?, Buzzfeed News, January 10, 2018, https://www.buzzfeed.com/alexkantrowitz/where-is-twitters-promised-ad-transparency-center; Google announced that it plans to release a transparency report about election ads alongside a database of those ads, and will “work to improve transparency of political issue ads and expand our coverage to a wider range of elections” over time. Kent Walker, Supporting election integrity through greater advertising transparency, Google: The Keyword, May 4, 2018, https://www.blog.google/topics/public-policy/supporting-election-integrity-through-greater-advertising-transparency/; Senators Mark Warner and Amy Klobuchar recently urged Coogle to “take this issue seriously and adopt similar commitments to [Twitter and Facebook] to enhance transparency for their users.” Shara Tibken, Senators urge Google, Twitter to be transparent about political ads, CNET, April 9, 2018, https://www.cnet.com/news/senators-warner-klobuchar-urge-alphabet-twitter-to-comply-with-honest-ads-act-like-facebook-will.

1

Facebook Business, Advertiser Help Center, When will my ad show with social information, https://www.facebook.com/business/help/1447178318880237?helpref=faq_content (last accessed March 22, 2018).

1

Facebook for Developers, Post, Graph API Version 2.12, https://developers.facebook.com/docs/graph-api/reference/v2.12/post (describing a post as “An individual entry in a profile’s feed.”) (last accessed March 7, 2018).

1

Facebook for Developers, Profile, Graph API Version 2.12, https://developers.facebook.com/docs/graph-api/reference/v2.12/profile (describing a profile as a “generic type that includes all of these other objects.”) (last accessed March 7, 2018).

1

Facebook profile types include Users, Pages, Groups, Events, and Applications. Facebook for Developers, Profile, Graph API Version 2.12, https://developers.facebook.com/docs/graph-api/reference/v2.12/profile (last accessed March 7, 2018).

1

Facebook for Developers, User, Graph API Version 2.12, https://developers.facebook.com/docs/graph-api/reference/user (last accessed March 7, 2018).

1

Facebook Business, Facebook Pages, https://www.facebook.com/business/products/pages (last accessed March 7, 2018).

1

See generally, Facebook Help Center, Basic Privacy Settings & Tools, https://www.facebook.com/help/325807937506242/ (last accessed March 7, 2018).

1

Facebook does allow pages to restrict access by age or geography, which allows page owners to comply with certain laws (e.g. “Pages promoting the private sale of regulated goods or services (including firearms, alcohol, tobacco, or adult products) must restrict access to a minimum age of 18.”). Facebook Pages Terms, https://www.facebook.com/page_guidelines.php (last revised March 8, 2018). Page owners used to be able to hide posts by using Facebook’s “dark posts” advertising feature, but the company effectively banned this practice with its existing ad transparency commitments. Casey Newton, This is Facebook’s self-defense plan for the 2018 midterm elections, The Verge, March 29, 2018, https://www.theverge.com/2018/3/29/17176754/facebook-midterm-election-defense-plan-2018.

1

Facebook Business, Business Manager Roles and Permissions, https://www.facebook.com/business/help/442345745885606 (last accessed March 7, 2018).

1

However, page administrators may choose to publicly share some or all of the identities of the users who manage that page. Facebook recently announced it would verify the identity of people who manage “large” pages. Mark Zuckerberg, April 6, 2018, https://www.facebook.com/zuck/posts/10104784125525891.

1

This requirement went into effect on November 14, 2017 to facilitate greater ad transparency. Facebook for Developers, Ad News, Business Manager API, Pages API, and Marketing API v2.11, November 12, 2017, https://developers.facebook.com/ads/blog/post/2017/11/07/marketing-api-v211/ (last accessed March 7, 2018). User profiles are not allowed to be used primarily for commercial gain. Facebook, Statement of Rights and Responsibilities, available at https://www.facebook.com/legal/terms/update (last accessed April 16, 2018) (“You will not use your personal timeline primarily for your own commercial gain, and will use a Facebook Page for such purposes.”)

1

Facebook for Developers, Page Feed, Graph API Version 2.12, https://developers.facebook.com/docs/graph-api/reference/v2.12/page/feed (last accessed March 7, 2018); Facebook for Developers, User Feed, Graph API Version 2.12, https://developers.facebook.com/docs/graph-api/reference/user/feed/ (last accessed March 7, 2018).

1

Facebook Help Center, How News Feed Works, https://www.facebook.com/help/327131014036297/ (last accessed March 7, 2018).

1

Nowhere in Facebook’s “Glossary of Ad Terms,” Facebook’s “Advertising Policies,” Facebook’s “Self-Serve Ads Terms,” Facebook’s “Data Policy,” nor in Facebook’s “Statement of Rights and Responsibilities,” does Facebook define “ad.” Other materials list some features of ads, but do not provide a full definition. See, e.g., Facebook, Glossary of Ad Terms, available at https://www.facebook.com/business/help/447834205249495/; Facebook, Advertising Policies, available at https://www.facebook.com/policies/ads/; Facebook, Self-Serve Ads Terms, available at https://www.facebook.com/legal/self_service_ads_terms; Facebook Full Data Policy, available at https://www.facebook.com/full_data_use_policy; Facebook, Statement of Rights and Responsibilities, available at https://www.facebook.com/legal/terms/update. Elsewhere, Facebook defines an ad as “paid messages from businesses that are written in their voice and help reach the people who matter most to them.” See Facebook, Help Center, Advertising Basics - About Facebook Advertising, available at https://www.facebook.com/business/help/714656935225188/.

1

Facebook describes ads as posts in its technical documentation and instructional materials. See, e.g., Facebook for Developers, Post, Graph API Version 2.12, https://developers.facebook.com/docs/graph-api/reference/v2.12/post (referring to “page posts created as part of the Ad Creation process.”) (last accessed March 7, 2018); Facebook Business, Using Page Insights, https://www.facebook.com/business/a/page/page-insights (referring to “people your post was served to, broken down by paid and organic reach.”) (last accessed March 7, 2018); Facebook Business, Advertiser Help Center, What is the difference between boosting a post and creating an ad?, https://www.facebook.com/business/help/community/question/?id=10203931386325374 (referring to ads as an opportunity to “send posts to people’s newsfeeds…”) (last accessed March 7, 2018).

1

Facebook allows advertisers to choose what kind of results they want to pay for. For example, advertisers can pay by ad impression, by clicks, or by watching a certain percentage of a video. Facebook Business, About the delivery system: When you get charged, https://www.facebook.com/business/help/146070805942156 (last accessed March 7, 2018). For more details on organic and paid distribution, see infra note 45 and accompanying text.

1

Facebook Ads Guide, https://www.facebook.com/business/ads-guide (last accessed March 21, 2018)

1

Facebook Ads Guide, “Image,” https://www.facebook.com/business/ads-guide/image (last accessed March 21, 2018). Ads that closely resemble user posts are sometimes called “dark posts.”

1

Facebook Business, “Reach new people and keep up with customers,” https://www.facebook.com/business/learn/facebook-create-ad-page-post-engagement/ (last accessed March 21, 2018).

1

Facebook, Help Center, “What’s the difference between organic, paid and post reach?” https://www.facebook.com/help/285625061456389 (last accessed March 21, 2018).

1

Making Ads Better and Giving People More Control Over the Ads They See, Facebook Newsroom, June 12, 2014, https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2014/06/making-ads-better-and-giving-people-more-control-over-the-ads-they-see/. However, research has shown these disclosures to be incomplete. Andreou et al, Investigating Ad Transparency Mechanisms in Social Media: A Case Study of Facebook’s Explanations, Network and Distributed Systems Security (NDSS) Symposium 2018, February 2018, http://lig-membres.imag.fr/gogao/papers/fb_ad_transparency_NDSS2018.pdf.

1

Facebook policies also refer to ads that have “stop[ped] running,” stating that ads can exist even after prioritized delivery has ended. Facebook, Self-Serve Ads Terms, https://www.facebook.com/legal/self_service_ads_terms (last accessed March 21, 2018).

1

Facebook Business, Choose your audience, https://www.facebook.com/business/products/ads/ad-targeting (accessed March 22, 2018).

1

Advertisers can input specific countries, state/regions, cities, postal codes, addresses, DMAs (designated market areas) or congressional districts. They can also add worldwide or global regions. Advertisers can target “people who live in this location,” “people recently in this location,” and “people traveling in this location.”

1

In the past, these categories were supplemented with data from third-party data brokers through a tool called “Partner Categories” since 2013. AdAge, Facebook to Partner With Acxiom, Epsilon to Match Store Purchases With User Profiles, February 22, 2013, http://adage.com/article/digital/facebook-partner-acxiom-epsilon-match-store-purchases-user-profiles/239. Facebook recently announced it would remove audience categories provided by third-party data brokers, but many predefined categories will remain, Drew Harwell, Facebook, longtime friend of data brokers, becomes their stiffest competition, The Washington Post, March 29, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-switch/wp/2018/03/29/facebook-longtime-friend-of-data-brokers-becomes-their-stiffest-competition/.

1

In each of these cases, personal information is anonymized (hashed) before being matched to Facebook users, so that Facebook does not learn about the people from the advertiser’s list, and advertisers do not know which specific user profiles on Facebook were matched to the people on their list. Advertisers can upload a list for Facebook to match against, or use tracking pixels to match Facebook users to off-Facebook activity. Facebook, Custom Audiences: Data Security Overview, https://3qdigital.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/facebook_audiences_data_security_overview.pdf (accessed March 21, 2018). According to Facebook’s terms, advertisers must have provided notice and received permission to include people in custom audiences. Facebook, Custom Audiences Terms, https://www.facebook.com/ads/manage/customaudiences/tos.php (accessed March 21, 2018). Facebook recently confirmed its plans to require advertisers to certify they have permission to use data for targeting, and make it more difficult to share Custom Audience data across multiple advertiser accounts. Josh Constine, Facebook plans crackdown on ad targeting by email without consent, TechCrunch, Mar 31, 2018, https://techcrunch.com/2018/03/31/custom-audiences-certification/.

1

Facebook Business, About Lookalike Audiences, https://www.facebook.com/business/help/164749007013531 (accessed March 22, 2018) (“When you create a Lookalike Audience, you choose a source audience…and we identify the common qualities of the people in it (ex: demographic information or interests). Then we find people who are similar to (or ‘look like’) them.”) Much of Facebook’s demographic and interest information is inferred based on behavior. As Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg described, “…we introduced value optimization, which helps businesses show ads to people who are most likely to spend based on previous purchase behavior. We also introduced value-based Lookalike Audiences, which use machine learning to help marketers reach people who are similar to their most valuable current customers.” Facebook, Inc. Second Quarter 2017 Results Conference Call, July 26th, 2017, https://s21.q4cdn.com/399680738/files/doc_financials/2017/Q2/Q2-‘17-Earnings-call-transcript.pdf.

1

The only characteristic advertisers may include in source lists is an indication of customer lifetime value. That way, Facebook knows to look for more people with higher lifetime values. Facebook Business, About customer lifetime value, https://www.facebook.com/business/help/1730784113851988 (accessed March 22, 2018).

1

In an advertising “Success Story,” Facebook describes how Libertarian presidential candidate Gary Johnson’s campaign “created Custom Audiences based on people who visited the candidate’s website, and then created lookalike audiences from those website visitors and people who purchased campaign merchandise,” which contributed to a “6.8-point lift in favorable opinions of Gary Johnson among moderates” and “3.5X more donations raised in 3 months, compared to entire (sic) 2012 campaign.” Success Stories: Gary Johnson for President, Facebook Business,https://www.facebook.com/business/success/gary-johnson-for-president.

1

Facebook, Enhancing Transparency In Our Data Use Policy, May 11, 2012, https://www.facebook.com/notes/facebook-and-privacy/enhancing-transparency-in-our-data-use-policy/356396711076884 (accessed March 21, 2018).

1

Facebook Business, Making Ad Metrics Clearer, February 22, 2018, https://www.facebook.com/business/news/making-ad-metrics-clearer.

1

Facebook Transparency Report, https://transparency.facebook.com/ (accessed April 16, 2018).

1

Hard Questions: Q&A with Mark Zuckerberg on Protecting People’s Information, April 4, 2017, https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2018/04/hard-questions-protecting-peoples-information/.

1

Rob Goldman, Update on Our Advertising Transparency and Authenticity Efforts, October 27, 2017, https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2017/10/update-on-our-advertising-transparency-and-authenticity-efforts/.

1

Elliot Schrage, Hard Questions: Russian Ads Delivered to Congress, October 2, 2017, https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2017/10/hard-questions-russian-ads-delivered-to-congress/.

1

See, e.g., Improving Enforcement and Promoting Diversity: Updates to Ads Policies and Tools, Facebook Newsroom, February 8, 2017, https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2017/02/improving-enforcement-and-promoting-diversity-updates-to-ads-policies-and-tools/ (“Over the past several months, we’ve met with policymakers and civil rights leaders to gather feedback about ways to improve our enforcement while preserving the beneficial uses of our advertising tools. … Our teams have worked closely with stakeholders to address these concerns by developing updates to our advertising policies, new advertiser education and stronger enforcement tools.”).

1

When Facebook was accused of suppressing conservative content in its Trending Topics section, it responded by turning entirely to automatically generated lists of topic stories — and failed to foresee how removing human oversight might speed up the spread of false and manipulative news stories. Dave Gershgorn and Mike Murphy, A glimpse into Facebook’s notoriously opaque — and potentially vulnerable — Trending algorithm, Quartz, August 31, 2016, https://qz.com/769413/heres-how-facebooks-automated-trending-bar-probably-works/.

1

For example, humanitarian and monitoring groups in Myanmar have accused Facebook of failing to detect and prevent the spread of religiously motivated hate speech and misinformation. Myanmar groups criticise Zuckerberg’s response to hate speech on Facebook, The Guardian, April 5, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/apr/06/myanmar-facebook-criticise-mark-zuckerberg-response-hate-speech-spread (“As far as we know, there are no Burmese speaking Facebook staff to whom Myanmar monitors can directly raise such cases [of incitement]…we urge you to invest more into moderation — particularly in countries, such as Myanmar, where Facebook has rapidly come to play a dominant role in how information is accessed and communicated.”).

1

Hearing Before the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary and the United States Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, April 10, 2018 (testimony of Mark Zuckerberg), available at https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/04-10-18%20Zuckerberg%20Testimony.pdf. See also, Robinson Meyer, Mark Zuckerberg Says He’s Not Resigning, The Atlantic, April 9, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/04/mark-zuckerberg-atlantic-exclusive/557489/ (“Well, I think what we need to do is be more transparent about what we’re seeing and find ways to get independent and outside experts to be able to come in, and contribute ideas on how to address these issues, like things that might be problems,” Zuckerberg said. “And then hold us accountable for making sure we do it.”).

1

Natasha Duarte, Emma Llansó, and Anna Loup, Mixed Messages? The Limits of Automated Social Media Content Analysis, 2018 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, https://cdt.org/files/2017/12/FAT-conference-draft-2018.pdf (“[Proposals to use automated review] wrongly assume that automated technology can accomplish on a large scale the kind of nuanced analysis that humans can accomplish on a small scale….natural language processing (NLP) tools still have major limitations when it comes to parsing the nuanced meaning of human communication, much less detecting the intent or motivation of the speaker.”).

1

See, e.g., Sheryl Sandberg, September 20, 2017, https://www.facebook.com/sheryl/posts/10159255449515177 (apologizing for anti-Semitic ad targeting categories on Facebook: “In order to allow businesses — especially small ones — to find customers who might be interested in their specific products or services, we offered them the ability to target profile field categories like education and employer. People wrote these deeply offensive terms into the education and employer write-in fields and because these terms were used so infrequently, we did not discover this until ProPublica brought it to our attention. We never intended or anticipated this functionality being used this way — and that is on us. And we did not find it ourselves – and that is also on us.”).

1

Sydney Li and Jamie Williams, Despite What Zuckerberg’s Testimony May Imply, AI Cannot Save Us, Electronic Frontier Foundation, April 11, 2018, https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2018/04/despite-what-zuckerbergs-testimony-may-imply-ai-cannot-save-us.

Related Work